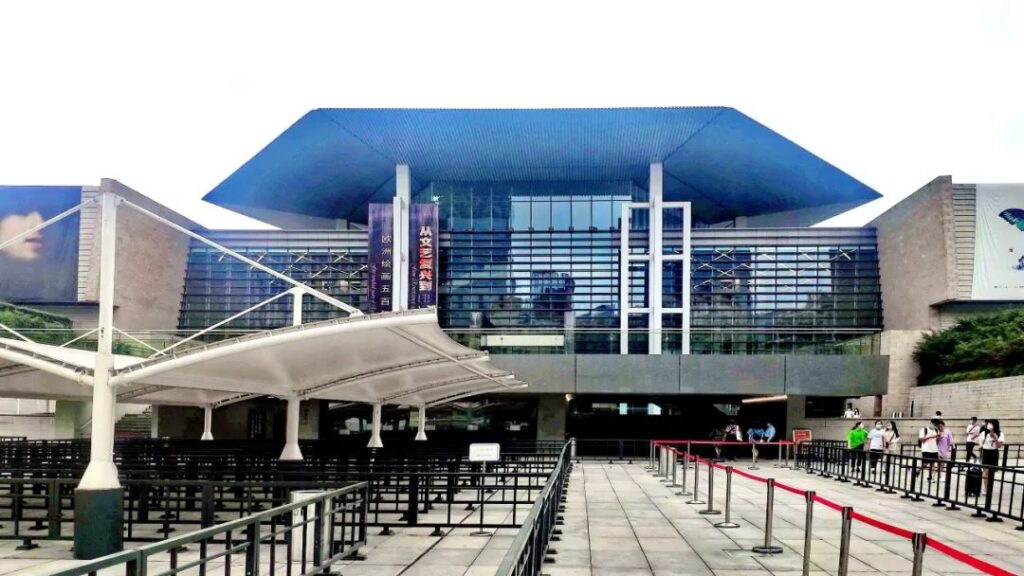

Whenever I travel, I always try to learn as much as possible about the local history and culture of each place I visit, and museums naturally become a must-see destination during my trips. During my visit to Changsha, the Hunan Provincial Museum was undoubtedly a place not to be missed. Located at the intersection of Defeng Road and Deya Road in Kaifu District, Changsha City, the Hunan Provincial Museum is the largest historical and art museum in Hunan Province and one of the first batch of national first-class museums.

Two exhibitions in the Hunan Provincial Museum are particularly worth seeing: the Three Xiang Historical and Cultural Exhibition and the Mawangdui Han Tomb Exhibition. “Xiang” is another name for Hunan, also known as “Three Xiang,” referring to the three prefectures of the ancient Hunan region in the Chu State: Dongting Prefecture in central Xiang, Qianzhong Prefecture in western Xiang, and Cangwu Prefecture in southern Xiang. Some also say it is a collective term for “Xiaoxiang, Zhengxiang, and Yuanxiang,” referring to the entire Xiang River basin, which is the Huxiang region.

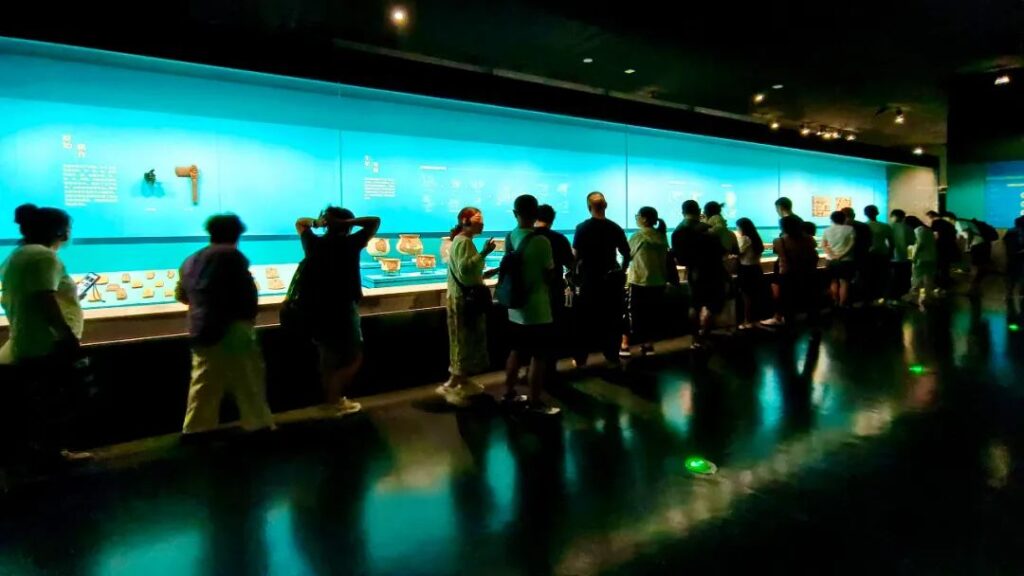

The Three Xiang Historical and Cultural Exhibition is located on the second floor of the museum. With the themes of “Home,” “Where I Come From,” and “Footprints of Life,” the exhibition showcases the ancient origins of the Hunan people and the Huxiang culture. Visiting the Three Xiang Historical and Cultural Exhibition allows me to gain an in-depth understanding of Hunan’s humanities, history, culture, folklore, and other knowledge.

The Huxiang culture originated from the Chu culture of the pre-Qin and Han dynasties. Qu Yuan’s poetry and the cultural relics from the Mawangdui tombs all have distinctive characteristics of the Chu culture. The true establishment of the Huxiang culture began with the Neo-Confucian school founded by the Northern Song dynasty literary figure and philosopher Zhou Dunyi. It was later developed by the thinker Wang Fuzhi in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, as well as the Qing dynasty thinker and politician Wei Yuan, before the Huxiang culture was constructed and matured.

As early as 500,000 years ago, humans were already living and thriving on this land of Hunan. According to legend, the Yan Emperor Shennong cultivated grains, wove hemp cloth, and made pottery here. Hunan got its name from being located south of Dongting Lake, and it is also known as Xiang for short because the Xiang River runs through it from north to south. Due to the nourishment of the Three Xiang and Four Waters, Hunan has a mild climate and rich soil. During the Five Dynasties period, it was already known as the “Autumn Wind Thousand Miles Lotus Land,” hence it is also called the “Lotus Land.”

According to research, Hunan has been engaged in rice farming since ancient times, from the early domestication of wild rice to the cultivation of artificial rice, and now to the cultivation of hybrid rice. From eating rice and fish soup to fashionable spicy flavors, the Hunan people’s taste for life and their use of utensils to convey the Dao (Way) are all condensed in the bronze wares of the Shang and Zhou dynasties used for rituals and music, the Chu and Han lacquerware that showcases the quality of life, the world-renowned Changsha kiln porcelain, and the Ming and Qing dynasty villages that pass on the tradition of farming and studying.

Inside the Hunan Provincial Museum, each classic cultural relic showcases the wisdom and diligence of the Chinese nation from ancient times to the present, allowing visitors to appreciate Hunan’s glorious history and immortal legends through those bronze wares, porcelain, lacquerware, agricultural tools, textiles, and other cultural relics. The Three Xiang Historical and Cultural Exhibition displays the spiritual heritage of the Hunan people from ancient times to the present through these precious cultural relics.

During the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the Hunan region had not yet been incorporated into the jurisdiction of the Central Plains dynasty. The indigenous ethnic groups such as the ancient Yue people, Pu people, and Ba people lived in the area. In ancient literature, the indigenous people were referred to as “Three Miao,” “Southern Man,” “Jing Man,” and so on. Later, people from the Central Plains crossed the Yangtze River and entered the middle and lower reaches of the Xiang and Zi rivers, bringing advanced bronze casting techniques to the area, thus initiating the bronze civilization of Hunan.

The Shang dynasty bronze boar-shaped zun (wine vessel), unearthed in Jiuhua, Xiangtan in 1981, is a wine storage vessel in the shape of a wild boar. Using a wild boar as the shape of the vessel is the only example among the existing Shang dynasty bronze wares. The boar zun has eyes that look straight ahead, exposed tusks, erect ears, thick limbs, and a drooping tail. An oval-shaped mouth is opened on the back of the boar zun, with a phoenix-shaped lid. The body of the vessel is largely decorated with scale patterns, and the front and back elbows are decorated with kui dragon patterns.

The Dahe human face pattern square ding (food vessel), cast in the late Shang dynasty, is the only ding in the country with human face patterns as decorations. The body of the ding is slightly rectangular, with bas-relief human faces on all four sides. The human faces are surrounded by cloud and thunder patterns, with horns on the sides of the forehead and claws on the sides of the chin. The inscription “Dahe” is cast on the inner wall of the ding’s belly, so the ding is also known as the Dahe square ding. Bronze wares from the Shang and Zhou dynasties mostly used animal faces as the main decorative patterns, making human face dings extremely rare.

The Minerwuan Bronze Square Lei, cast in the late Shang dynasty, is a wine-holding vessel among wine vessels. The inscriptions “Minerwuan made this respectful vessel for Father Ji” and “Min made this respectful vessel for Father Ji” are cast inside the lid and the vessel respectively, earning it the title “King of Square Lei.” The lei was unearthed in 1922, with the lid remaining in China while the body flowed overseas. In 2014, after much communication and agreement, the body was brought back to China at a price of 20 million US dollars, reuniting the body and lid.

The Four Sheep Square Zun (replica), with the original stored in the National Museum of China, is a wine vessel used for rituals. Zun is usually round, with a bulging mouth and a large opening, and square ones are rare. The Four Sheep Square Zun is one of the few square zun, standing 58 cm tall. The square mouth opens slightly like a trumpet flower, with four sheep heads surrounded by flying dragons at the waist, and a stable trapezoidal base. The entire vessel has a simple shape and beautiful lines, making it a rare and precious treasure.

The Bronze Zun with Ox Head and Beast Face Pattern, cast in the late Shang dynasty, is a national treasure retrieved from a garbage dump. In 1962, Hunan cultural relic workers accidentally discovered this bronze zun at a waste copper purchasing station. At that time, the bronze zun was severely fragmented, and it was only after careful restoration that it was restored to its original appearance. The Bronze Zun with Ox Head and Beast Face Pattern is the tallest among similar bronze zun, representing the extremely high level of art and technology that Hunan had reached in the early Bronze Age.

As the Hunan region entered the civilized period, the indigenous people and the immigrating outsiders gradually blended, forming the Han ethnic majority in Hunan. Later, with the expansion of the Chu state’s power, its territory in Hunan expanded from the southern shore of Dongting Lake in the early Spring and Autumn period to the central and southern Hunan regions. The Chu people and the indigenous people integrated, fostering a unique regional culture in Hunan.

Since the Qin and Han dynasties, whenever there was turmoil in the Central Plains, a large population would migrate from the north to Hunan. The transition between the two Jin dynasties, the late Tang dynasty, and the end of the Northern Song dynasty were three important stages of northerners migrating south, with Hunan being an important place for people to stay. The northerners brought advanced production techniques and culture, promoting the rapid development of Hunan’s economy and culture. The integration of indigenous people and immigrants fostered a diverse ethnic culture.

“Jiangxi fills Huguang, Huguang fills Sichuan” is a famous migration event in Chinese history. At the end of the Yuan and the beginning of the Ming dynasty, years of war left Hunan’s fields desolate and its people scattered, with many places being uninhabited. Therefore, the Ming dynasty moved a large number of immigrants from nearby Jiangxi to Hunan. At the end of the Ming and the beginning of the Qing dynasty, frequent battles between Zhang Xianzhong and the Qing army in Sichuan caused the population of Sichuan to be nearly wiped out and the fields to be desolate. The Qing court issued an edict, forcing many people from Huguang to relocate to Sichuan.

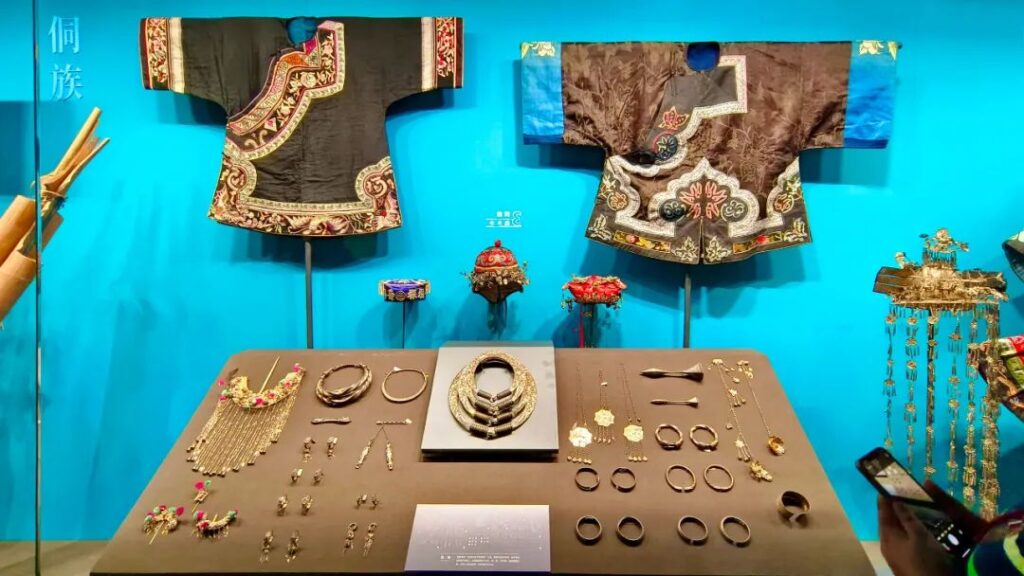

Today’s Hunan is a multi-ethnic province with more than 50 ethnic minorities, 11 of which are indigenous. The other ethnic minorities migrated to Hunan for various reasons. The indigenous ethnic minorities mainly live in the mountainous areas of western, southern, and eastern Hunan, accounting for 10% of Hunan’s total population. Among Hunan’s various ethnic minorities, the Miao and Tujia have the largest populations.

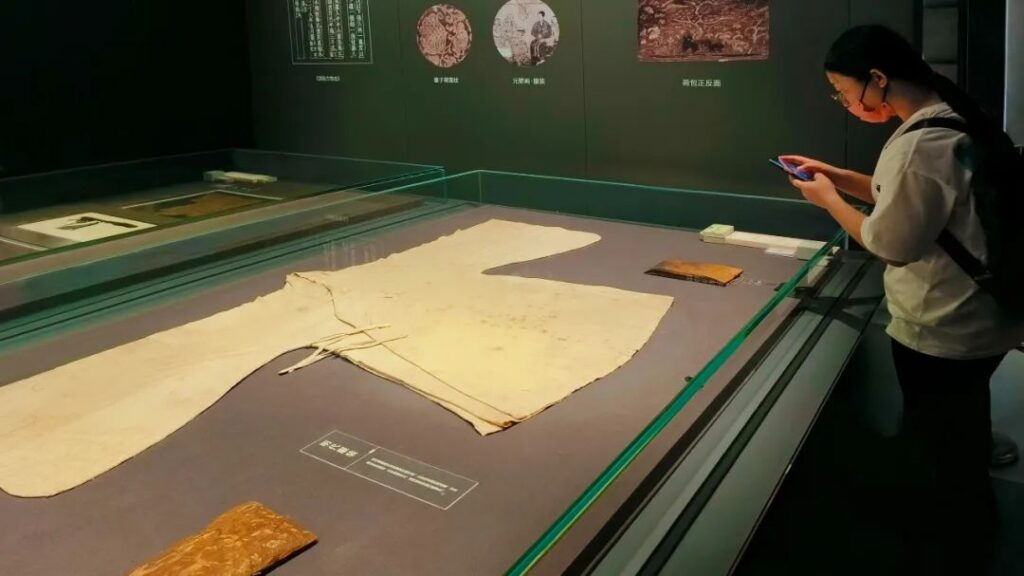

“Yao Nvshu,” prevalent in Jiangyong County, Hunan Province, is a mysterious and peculiar script used only among women and incomprehensible to men. It is also the world’s only script exclusively for women’s use. Nvshu describes marriage, family, personal emotions, songs, and riddles from a female perspective. It is the “women’s kingdom” in the realm of writing and a unique and precious treasure of Chinese culture.

The museum houses a large collection of Chu swords. It is said that during the Eastern Zhou period, the Chu people admired the charm of the famous swords of Wu and Yue, and were devoted to imitating them, achieving remarkable success. By the middle of the Warring States period, Chu had conquered Yue, encompassing its famous swords, treasures, and skilled craftsmen, making Chu swords another pinnacle of ancient Chinese swords in the pre-Qin period. The custom of men wearing swords was prevalent in Chu. The Chu people were fond of swords, with the habit of wearing swords, the custom of gifting swords, and the practice of burying swords.

The Chu region was fond of shamanism. In the sacrificial rituals of the Shang and Zhou dynasties, musical instruments were more important than ritual vessels, with bronze cymbals being the most distinctive. They were tall, heavy, and had their own evolutionary system. The vast majority of bronze cymbals were unearthed in the Xiangjiang River Basin, suggesting that Hunan may be the place of origin. The exhibition hall displays many bronze chime bells. Next to the chime bells, there is also a “Bronze Boar Chime Stone.” In the ritual and music system of the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the users of chime stones held very high ranks.

The Warring States “Lacquered Wooden Drum Stand with Tiger Seat and Phoenix Bird” (replica) was an object enjoyed by the high-ranking nobility in Chu and a unique musical instrument of the Chu state. The Chu region revered the phoenix. In the minds of the Chu people, the phoenix was the supreme divine bird. The phoenix bird on the wooden drum stand stands tall with its head held high, as if it were adding strength to the drum’s sound. The king of beasts, the fierce tiger, crouches at the feet of the phoenix bird, perhaps to highlight the majesty and awe-inspiring effect of the phoenix’s cry to the ninth heaven.

The “Warring States Bronze Lamp with Kneeling Figure” is similar to today’s candlestick. It can be seen that the entire lamp is divided into three parts: the kneeling figure, the lamp stand, and the lamp plate. In the Shang and Zhou periods, people’s living habits were to sit on the ground. The ancient people’s “sitting” was kneeling, specifically referring to placing both knees on the mat, with the buttocks resting on the heels. If the buttocks leave the heels and the heels are upright, it is called “ji zuo” (kneeling with buttocks off the heels).

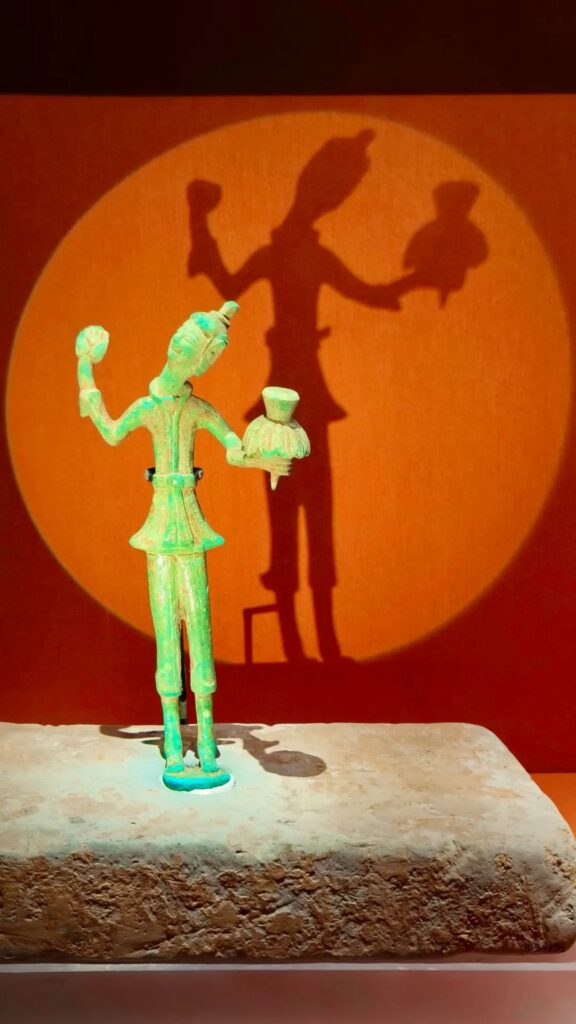

In a corner of the exhibition hall, I was drawn to an interesting “small figurine.” This is a national treasure from the Southern Dynasties, the “Bronze Dancing Figurine.” The dancing figurine stands with both feet on a brick seat, head tilted upward in a laughing expression, holding a lotus-like object in the left hand, and raising a clenched fist with the right hand. This dancing figurine is vivid in shape and provides important evidence for studying the history of Chinese dance, the forms of singing and dancing, and the costumes of the Southern Dynasties period.

Hunan is the province in China that started rice cultivation the earliest. As early as the Shang Dynasty, Hunan began large-scale rice cultivation. In 1988, rice husks dating back about 9,000 years were found in pottery unearthed at the Pengtoushan site in Li County, while the rice discovered at the Hemudu site in Zhejiang only dates back about 7,000 years, which further broke the previous “Indian theory” of rice origin.

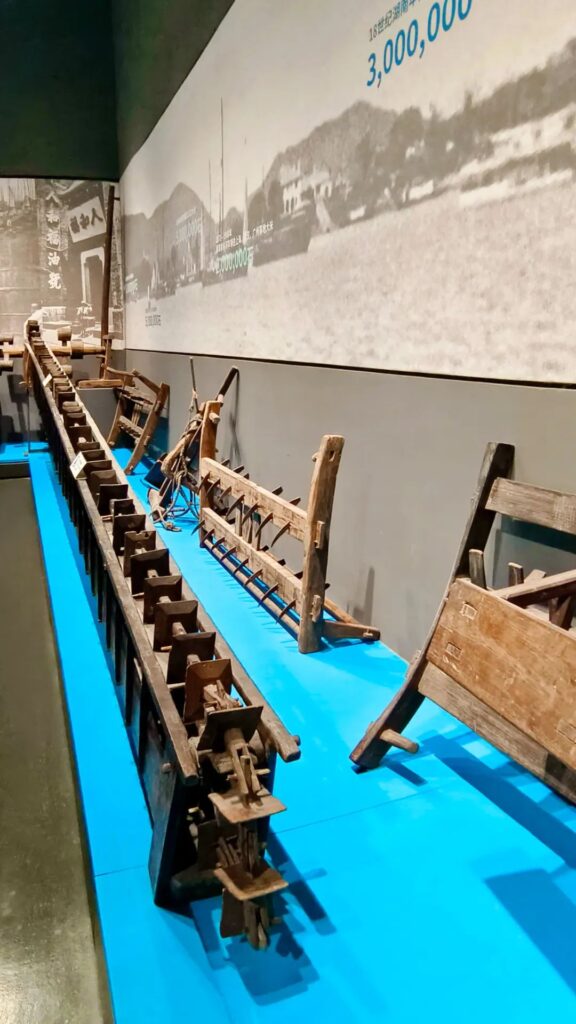

During the Tang and Song dynasties, the economic center shifted southward, and Hunan’s position in grain production gradually became prominent. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Hunan’s arable land expanded, and grain output increased dramatically, making it a major grain supply area in the country. During the Kangxi period, it was crowned as “the first rice-exporting region in the world,” and during the Qianlong period, there was a folk saying, “When Hunan is ripe, the world has enough.” The ships transporting grain were endless, and in places like Changsha and Xiangtan, “warehouses were lined up, and rice bags blocked the way,” “piled up like mountains and sold like rivers.”

The abundance of grain brought a rich and colorful lifestyle. The exhibition hall displays a variety of cooking utensils, drinking vessels, and tableware made of pottery, bronze, lacquerware, and other materials. The earliest pottery unearthed in Hunan can be traced back to 15,000-13,000 years ago. The emergence of pottery solved the problem of rice storage and cooking, which in turn promoted the development of rice agriculture.

During the Tang Dynasty, as the connection channel between Guangzhou, the seaport for foreign trade, and the capital city, Hunan was deeply influenced by foreign cultures. Particularly in the mid-late Tang Dynasty, when foreign trade routes shifted from land to sea, Hunan had closer exchanges with foreign cultures, leaving their mark on daily necessities and living customs. The porcelain produced had strong foreign cultural characteristics.

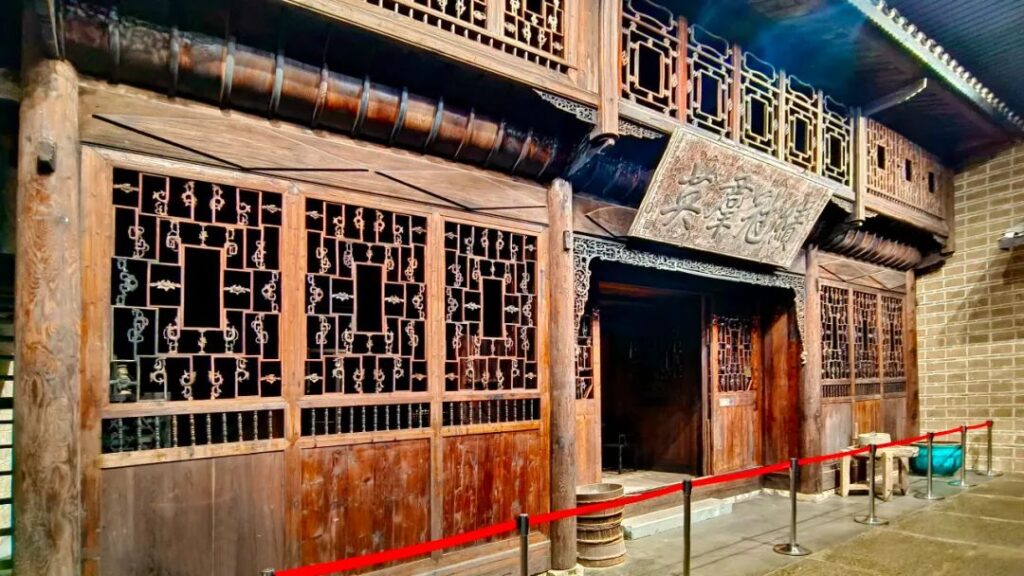

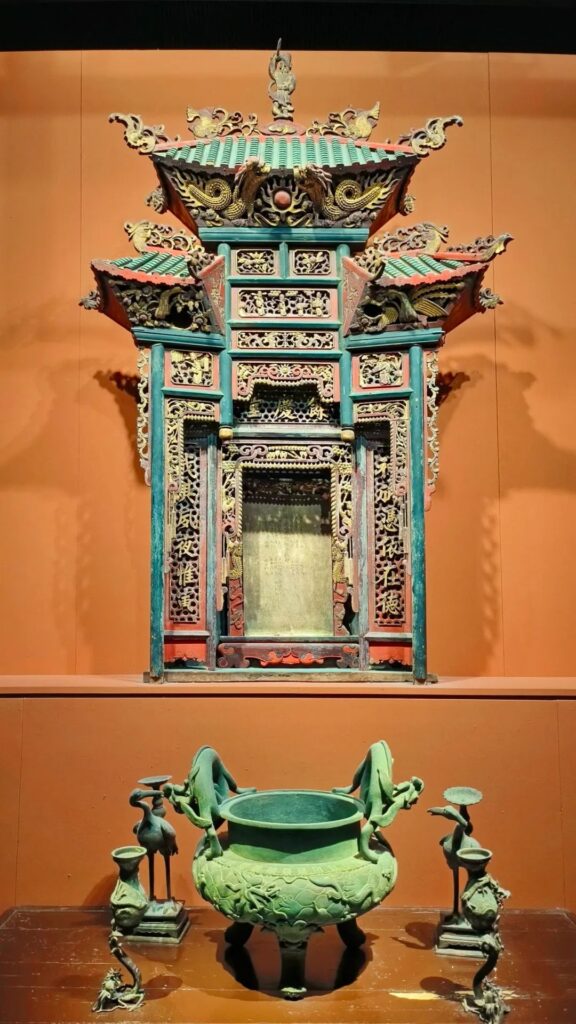

The museum houses a complete two-story house. This building was constructed during the Jiaqing period of the Qing Dynasty, with a simple and natural architectural style and a well-preserved structure. The carvings on the house are exquisite, making it a typical representative of ancient Hunan architecture. This two-story wooden building was originally a residence in Huaihua, Hunan. In 2010, when a hydropower station was being built in the area, this old house was set to be demolished. The museum acquired this set of old houses, completely dismantled them, and restored them in the museum.

The Qing Dynasty gold-plated carved shrine is a cabinet used in ancient times to enshrine statues of gods or ancestral tablets. Shrines are generally common in ancestral halls and are carved out of wood. The shrine collected by the Hunan Provincial Museum is exquisitely carved, with upturned eaves and multiple layers. Each layer is embossed and carved with auspicious animals such as flying phoenixes, eagles, and spotted deer.

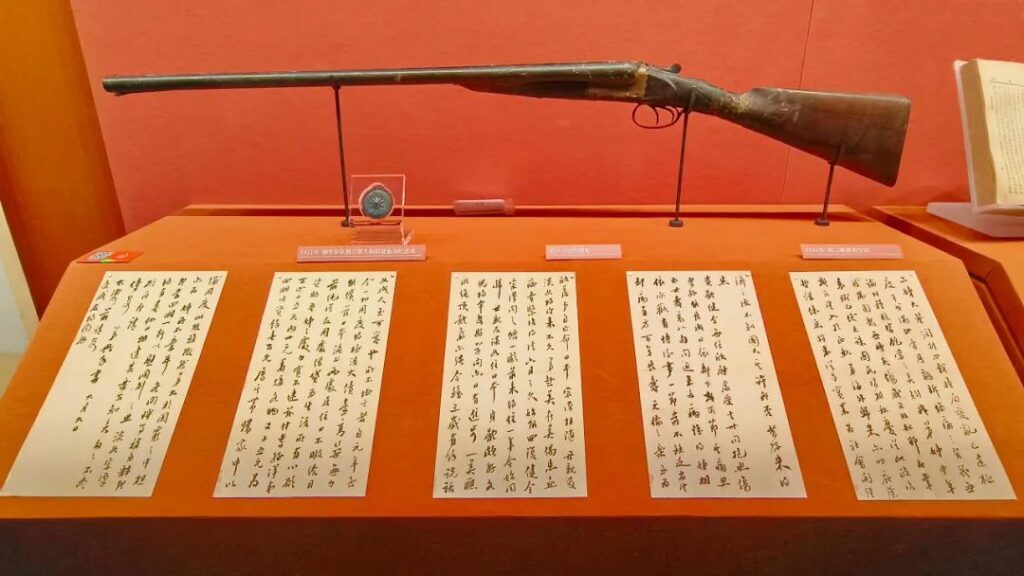

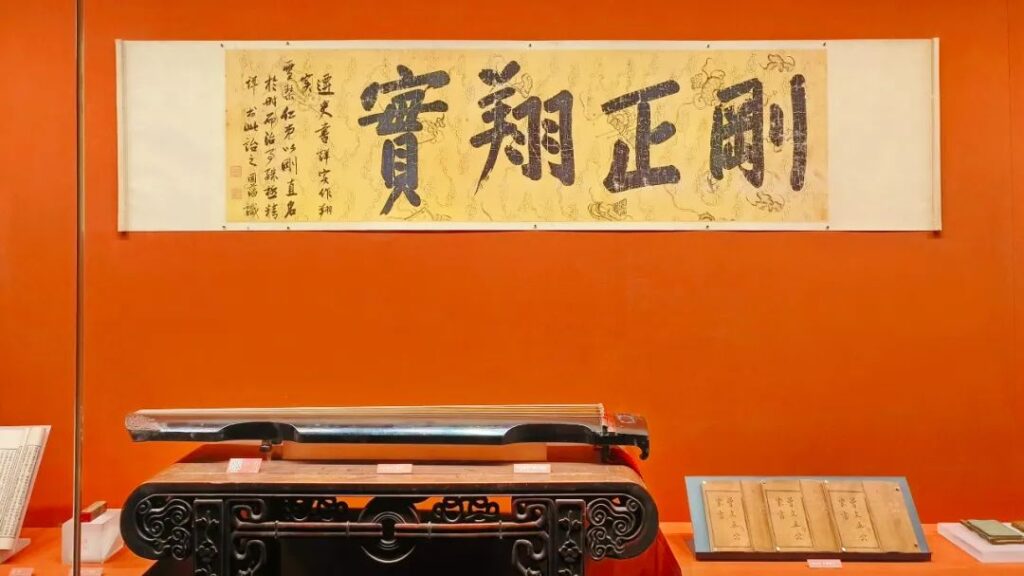

In the final section of the exhibition on the historical and cultural relics of the three Xiang regions, it showcases how over thousands of years, the influence of patriotic and people-oriented thoughts, the infiltration of Central Plains culture, the inheritance of academy education, and the agitation of modern ideas have shaped the Hunanese people’s personality of being outspoken, daring to be the first, loyal and trustworthy, and fearless in the face of death for the sake of the country. Hunan culture, as a distinctive and stably inherited cultural form, has nurtured the humanistic wonder of the eruption of talents in Hunan in modern times.

The historical and cultural heritage of the three Xiang regions is the “soul” of Hunan. The stubborn and straightforward character of the Hunan indigenous people, the pioneering spirit of the immigrants from all dynasties who endured hardships, coupled with the influence of the culture of Qu Yuan and Jia Yi, and the inheritance and accumulation of Confucian academies, have shaped the “simple and righteous” and “self-improvement” Hunan culture. The spirit of the Hunanese people, who dare to be the first, use their knowledge to serve society, and face death without fear, is inseparable from Hunan culture.