Whenever I travel, I always strive to understand the local history and culture of each place I visit, and museums naturally become a must-see destination. During my recent trip to Changsha, the Hunan Provincial Museum was undoubtedly a place I could not miss. Located at the intersection of Dongfeng Road and Deya Road in Kaifu District, Changsha City, it is the largest historical and artistic museum in Hunan Province and one of the first national first-grade museums.

Within the Hunan Provincial Museum, the Mawangdui Han Tombs exhibition is the most valuable and fascinating. The Mawangdui Han Tombs, excavated in Changsha from 1972 to 1974, yielded more than 3,000 artifacts, including lacquerware, pottery, silk textiles, silk books, silk paintings, and traditional Chinese medicines. They also contained a well-preserved female corpse. The Mawangdui Han Tombs were later rated as one of the “Top Ten Ancient Tombs with Rare Treasures in the World.”

In the early Western Han Dynasty, Wu Rui, a founding hero, was changed from the King of Hengshan to the King of Changsha. The area under his jurisdiction inherited the Changsha and Qianzhong commanderies from the Qin Dynasty. Wu Rui made Xiangxian, the former Qin Changsha commandery, the capital of the Changsha Kingdom. This was the first vassal state in Hunan’s history. The Mawangdui Han Tombs are the burial sites of Li Cang, the prime minister of the Changsha Kingdom, and his family members during the early Western Han Dynasty.

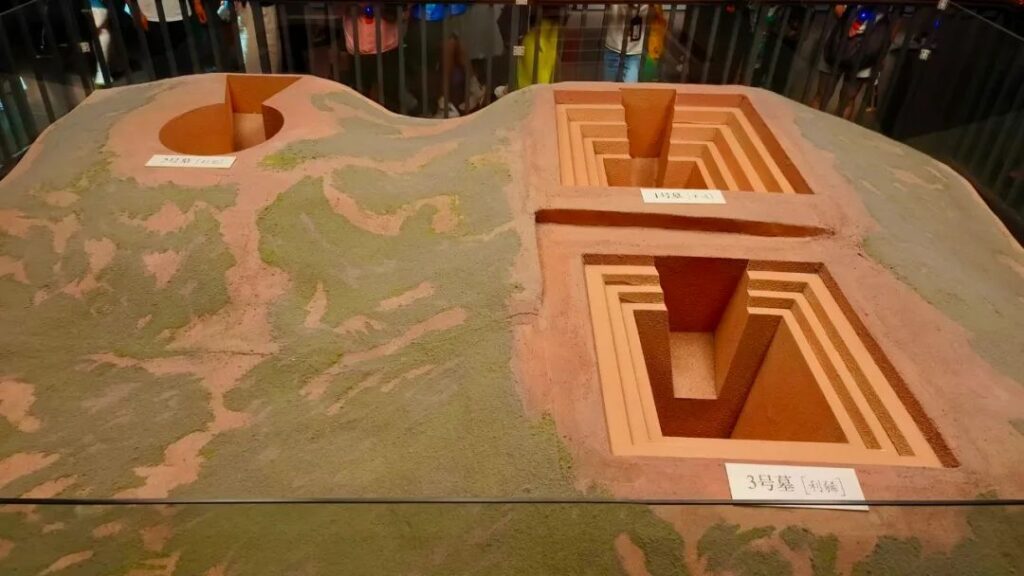

There are three tombs in Mawangdui. Tomb No. 2 belongs to Li Cang, the prime minister of the Changsha Kingdom, while Tomb No. 1 belongs to his wife, Xin Zhui, and Tomb No. 3 belongs to his son, Li Xi. During the excavation, it was discovered that both Li Cang’s and Li Xi’s tombs had been damaged by tomb raiders, but Xin Zhui’s tomb remained untouched and was thus exceptionally well-preserved. The Mawangdui Han Tombs provide essential material evidence for studying the history, culture, and social life of the early Western Han Dynasty.

The artifacts displayed in the museum are the cream of the crop from the Mawangdui Han Tombs. The lacquerware represents the highest level of lacquer craftsmanship in the early Han Dynasty, while the silk textiles showcase the achievements of Han Dynasty textile technology. The silk paintings depict the mysterious heavenly realm and the desire for immortality, and the silk books pass down the knowledge and wisdom of ancient sages. The female corpse is a miracle in the history of human mummification.

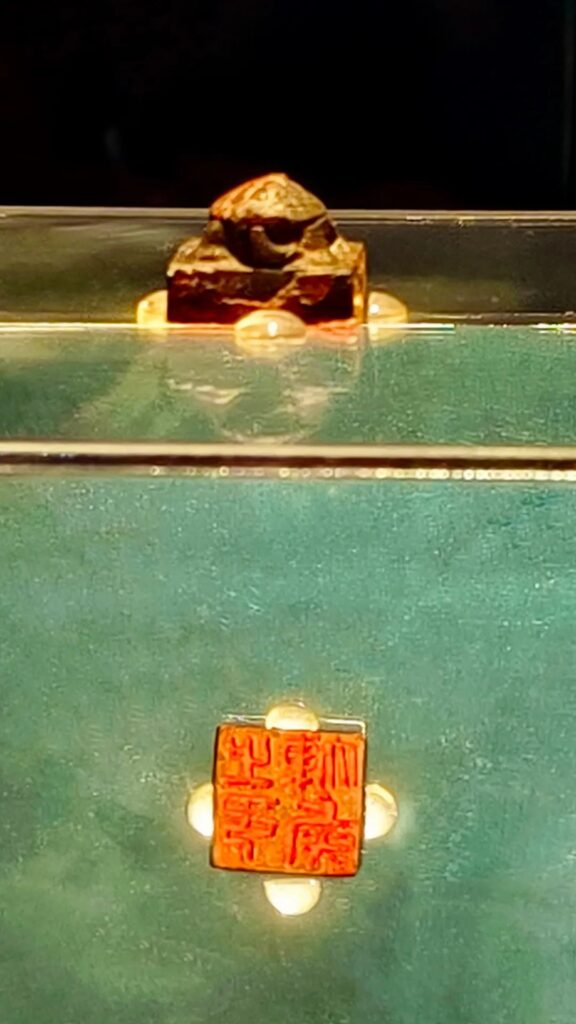

Three seals were unearthed from Li Cang’s tomb: a jade personal seal inscribed with “Li Cang” and two bronze official seals engraved with “Seal of the Marquis of Sui” and “Prime Minister of Changsha.” The Marquis of Sui refers to Li Cang, whose fief was in Sui County, hence the title Marquis of Sui. Based on the burial system of the Han Dynasty, the artifacts inscribed with “Marquis of Sui’s Household” and “Prime Minister of the Marquis of Sui’s Household,” and the personal seal of “Concubine Xin Zhui” unearthed from Xin Zhui’s tomb, the tomb owner was confirmed to be Li Cang, the prime minister of the Changsha Kingdom.

The vermilion-lacquered coffin excavated from Xin Zhui’s tomb is coated with vermilion lacquer inside and out. The exterior is decorated with auspicious patterns such as dragons, tigers, vermilion birds, deer, and immortals in cyan, pink-brown, lotus-root-brown, reddish-brown, and yellowish-white lacquer. The use of red and the immortal realm symbolize that the deceased has escaped the harassment of evil spirits and reached the realm of immortality. The painting style on the lacquered coffin is free-flowing and lively, with bold and clean lines, representing the high level of achievement in Han Dynasty lacquerware craftsmanship.

The black-lacquered painted coffin features mythical beasts traversing through flowing clouds. The interior of the coffin is coated with vermilion lacquer, while the exterior has a black lacquer background. Using colors such as vermilion, white, black, yellow, and green, the coffin depicts dynamic and flowing clouds, with over a hundred animals and mythical creatures of various shapes interspersed among them, forming 57 different scenes. This is a typical example of Han Dynasty cloud-pattern lacquer painting.

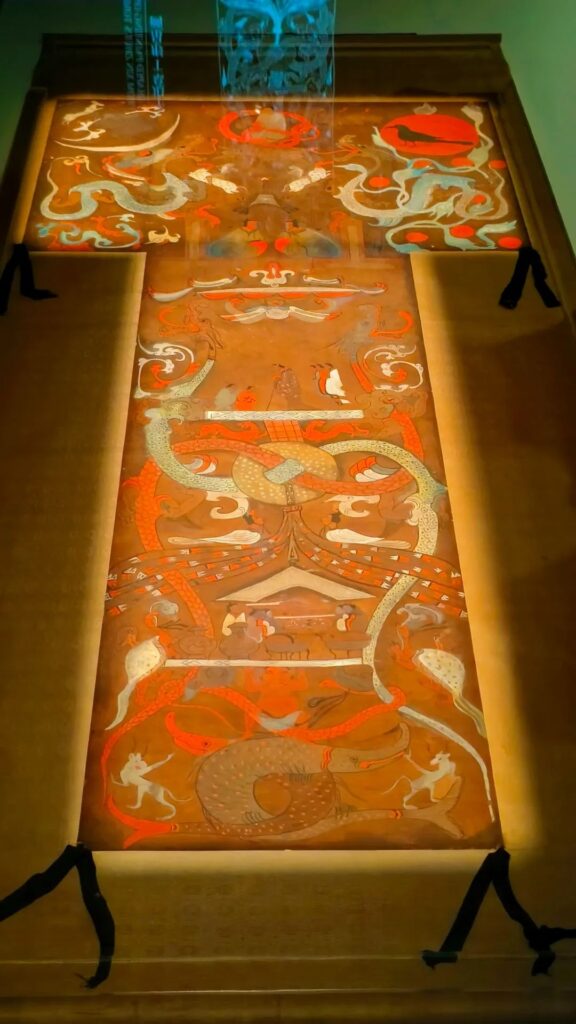

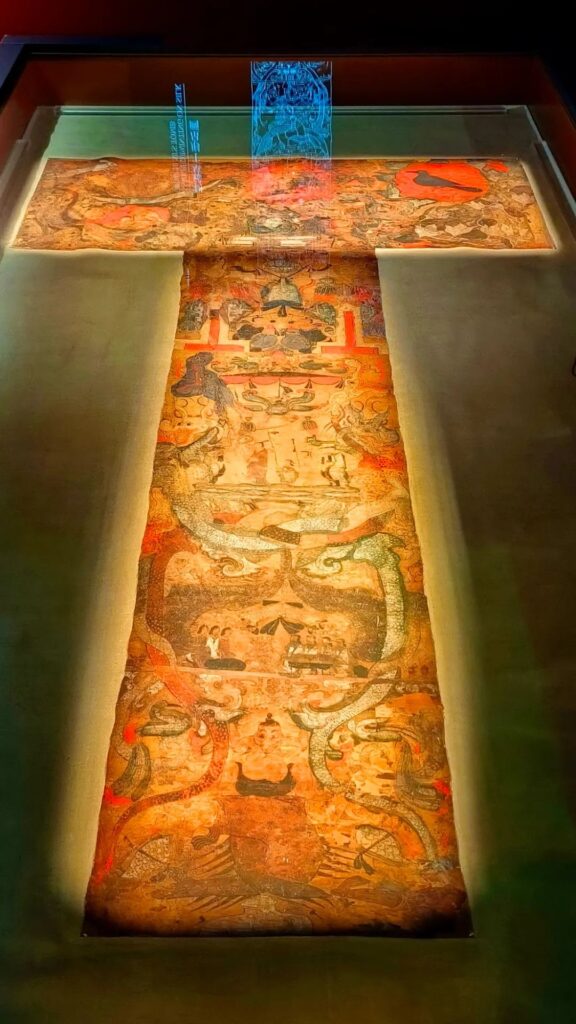

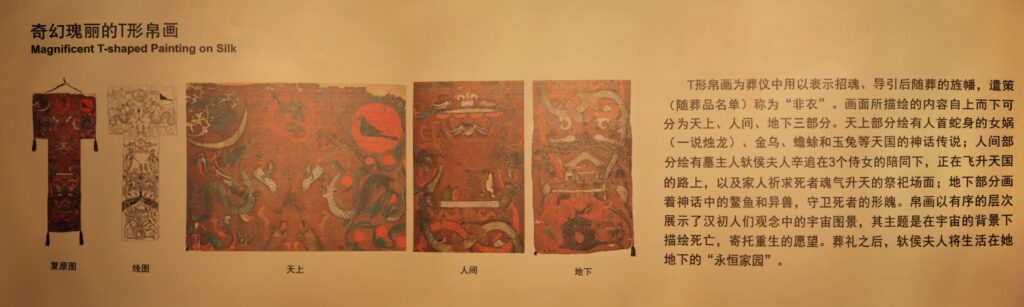

During the excavation of Xin Zhui’s tomb, a T-shaped silk painting was discovered on the lid of the innermost coffin on the fourth layer. The painting is divided into three parts: the heavens, the human world, and the underworld. The heavens depict nine golden birds (the sun), a toad (the moon), and a flood dragon, while the human world shows an elderly woman slowly ascending to the heavens, accompanied by three maids. The underworld features a giant figure supporting the heavens and the earth, expressing the ancient people’s imagination of the heavenly realm and their pursuit of immortality.

During the excavation of Li Xi’s tomb, another silk painting was discovered on the lid of the innermost coffin on the third layer. The layout of this painting is slightly different from the one in Tomb No. 1. In the heavens, there is only one sun and a sky full of stars, with the heavenly gate moved to the center. The flood dragons are not interlocked with a jade disc, and their heads are facing away from each other. The human world section depicts the tomb owner wearing a red robe and a long sword at his waist, while the underworld features a giant figure grasping dragons with both hands. These two paintings are believed to be spiritual mediums, guiding the tomb owner to enter the heavenly realm after death.

The T-shaped silk painting, also known as “feiyi,” is made by stitching three pieces of single-layer fine silk together. A bamboo pole is wrapped horizontally at the top, with silk ribbons attached, allowing it to be displayed. The middle and lower parts have dark blue and black hemp ribbons at the four corners. As the painting includes a portrait of the deceased, it was considered a “soul banner,” leading the way during the funeral procession and placed on the lid of the innermost coffin during the burial.

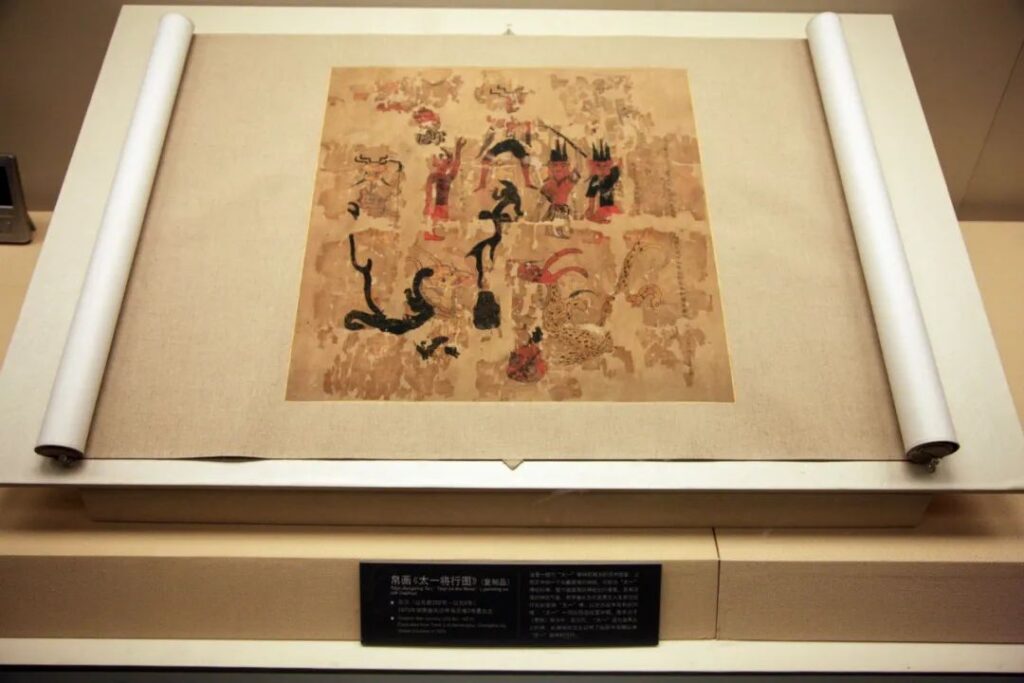

The “Taiyi Xingxing Tu” silk painting is a remnant of the silk painting on the east wall of the coffin chamber in Li Xi’s tomb. The upper center depicts a “Taiyi” deity wearing deer antlers, with two attendants on each side below the deity. Additionally, there is a yellow-headed blue dragon serving as a mount, with blue and yellow dragons acting as left and right wing guards, and the Thunder God and Rain Master as left and right vanguards. The entire painting portrays the deity’s procession, imbued with a strong mythical atmosphere.

The “Bingmache Xing Tu” silk painting, unearthed from Li Cang’s tomb, is 219 centimeters long and 99 centimeters wide, making it the earliest surviving realistic scroll painting in Chinese art history. In the upper left corner, two rows of guards escort the tomb owner, who wears a long crown and a long sword at his waist, as he slowly proceeds. The lower left shows a square formation and a scene of drumming and bell-ringing. The upper right features an orderly chariot formation, while the lower right displays a cavalry formation. All formations are facing the tomb owner, seemingly conducting a sacrificial or inspection ceremony.

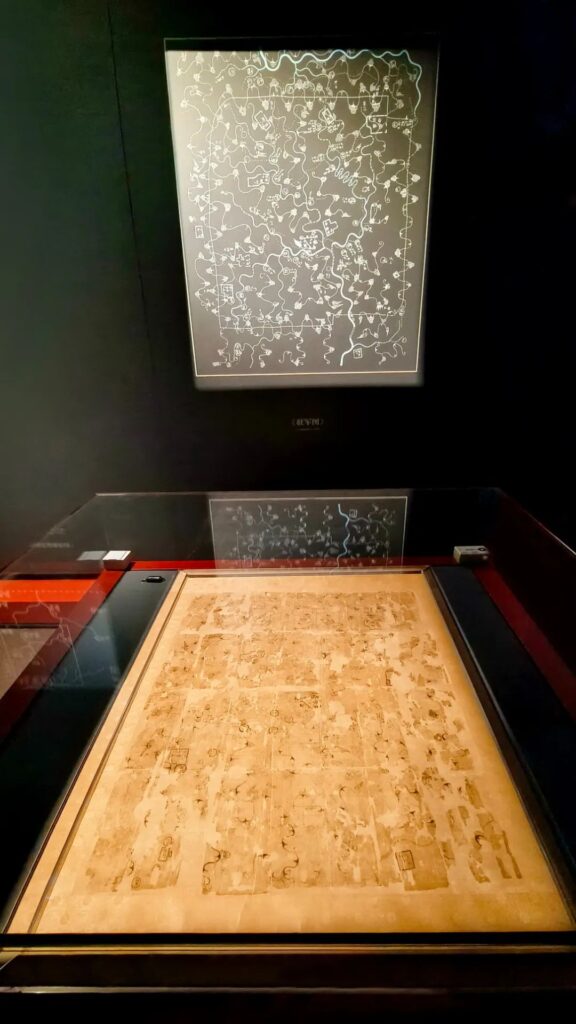

In Li Cang’s tomb, two of the world’s earliest maps were unearthed, with astonishingly precise surveying and mapping. The “Terrain Map” is the earliest surviving color map, using a method similar to modern contour lines and closed curves to depict the terrain of a certain area in the Western Han Dynasty in detail. The “Garrison Map” provides a detailed description of military deployment, using three colors to distinguish the important divisions during military deployment at that time.

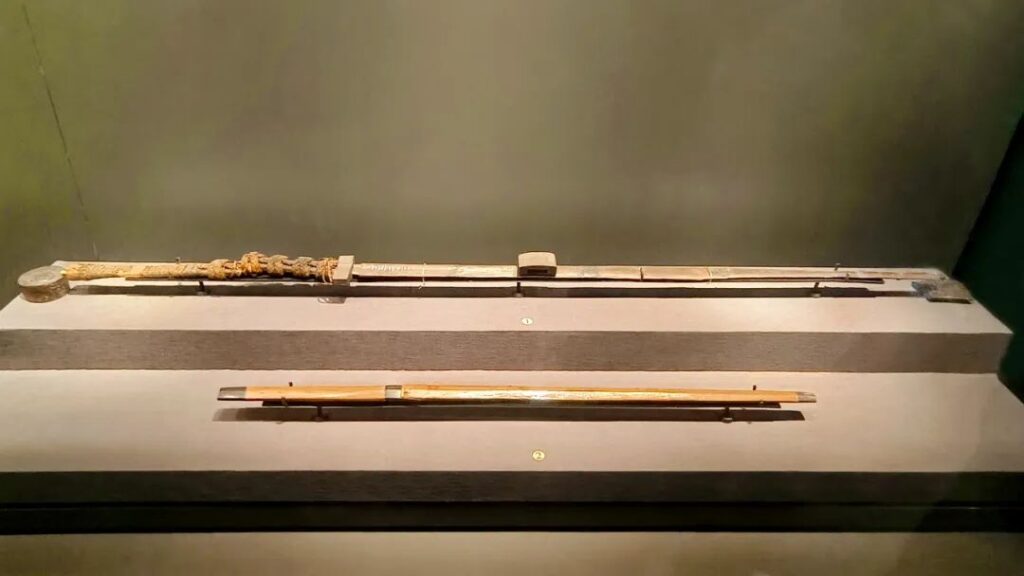

The horn long sword and horn short sword, both made of ox horn and serving as burial objects, were excavated from the Tomb No. 3 of Li Xi, Li Cang’s son. The long sword is the longest sword discovered in Chu and Han tombs to date. People in the Han Dynasty liked to wear swords, both for self-protection and as decorations. The prevalence of wandering swordsmen in the early Han society further popularized the custom of wearing swords.

The Han Dynasty was a golden age for the lacquerware industry in ancient China. Lacquerware had become the primary household utensils at that time, and its status was gradually replaced only after the widespread emergence of porcelain. Over 700 exquisite pieces of lacquerware were unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tombs, setting records in China for the concentration and quantity of lacquerware finds, fully reflecting the prosperity of the lacquerware industry in the Changsha area during the early Western Han Dynasty.

The types of lacquerware unearthed mainly include tripod cauldrons (ding), boxes, pots, wine vessels (zhong), cups (zhi), spoons, knives (bi), ear cups, plates, cosmetic boxes (lian), tables, and cup boxes, among which ear cups and plates are the most common. The vast majority of the lacquerware has a wooden core, and the patterns are mostly geometric, with a small number of floral and realistic animal patterns. The main methods used to create the patterns include lacquer painting, oil painting, and incised drawing, with some pieces also employing the “lacquer piling” technique.

The cloud and bird pattern lacquer wine vessel (zhong) was unearthed from the tombs of Xin Zhui and Li Xi. When excavated, the vessel still contained residues of alcoholic beverages. The funeral inventory list referred to it as a “lacquer painted fang,” specifying that it was used to “hold white wine” or “hold rice wine.” This cloud pattern lacquer zhong has a black lacquer exterior and a red lacquer interior. It features a straight mouth, flat rim, a collar around the mouth, a bulging belly, and a ring foot.

The cloud pattern lacquer wine vessel (zhong), unearthed from the tombs of Xin Zhui and Li Xi, is also a wine container. When excavated, the zhong contained residues of alcoholic beverages. The bottom of the vessel bears the character “shi” written in red, indicating a Han Dynasty measure of 120 jin, equivalent to 13.5 kilograms today. The measured capacity of the vessel is 19.5 liters. The funeral inventory list records that it was used to “hold warm wine,” which is a low-alcohol wine made by fermenting rice wine qu, similar to modern-day sweet wine.

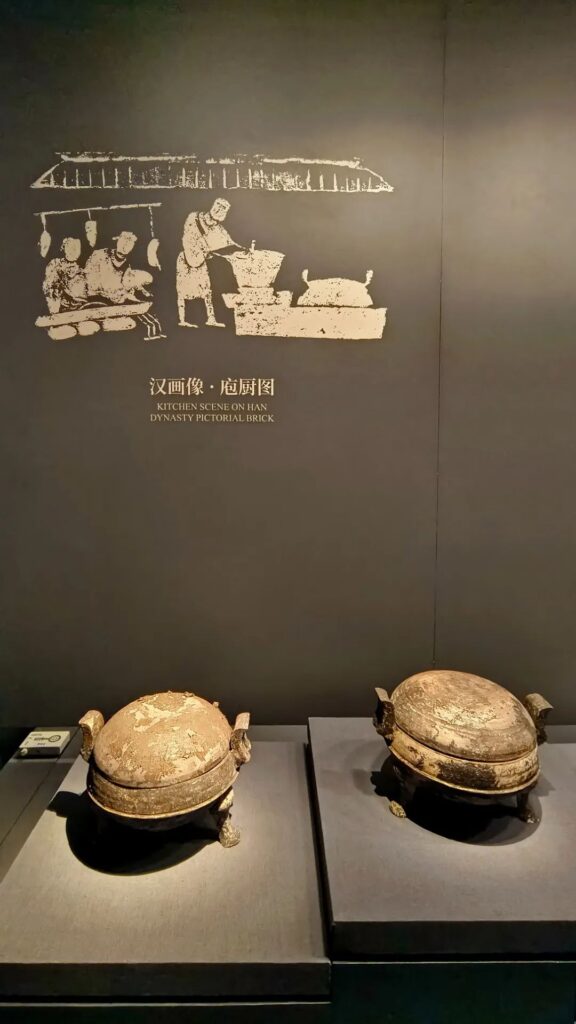

The cloud pattern lacquer tripod cauldron (ding) has an elliptical spherical shape, with a spherical lid featuring three orange ring-shaped knobs. The lid and the body of the cauldron are connected by a mortise and tenon joint. The cauldron has a bulging belly and a slightly rounded bottom. Two straight ears are attached to the mouth of the vessel, and it stands on three animal hoof-shaped feet. The exterior of the cauldron is coated with black lacquer, while the interior is coated with red lacquer. The feet are decorated with animal face patterns painted in red lacquer, and the two ears feature cloud patterns. The bottom of the cauldron is inscribed with the characters “er dou” in red, indicating the vessel’s capacity.

The cloud pattern lacquer ear cup is a food and drink container made from carved wood. It has an elliptical shape, a round rim, a small flat bottom, and slightly upturned crescent-shaped double ears. The interior of the cup is coated with red lacquer and features rolled cloud patterns painted in black lacquer. The bottom of the cup is inscribed with the characters “jun xing jiu” in black lacquer, meaning “please enjoy the wine.” The exterior and the bottom of the cup are coated with plain black lacquer without any patterns. The outer part of the rim and the top of the two ears are decorated with geometric cloud patterns in red and ochre colors. The back of the ears is inscribed with the characters “yi sheng” in red, indicating the capacity of one sheng. The funeral inventory list refers to it as a “small cup.”

The black background with red cloud pattern lacquer plate is a flat plate used for serving food. It is made from turned wood and has straight walls and a flat bottom. The interior of the plate is coated with two sets of red and black lacquer. The black lacquer is used to paint cloud and dragon patterns, with spiral patterns forming the dragon’s whiskers, horns, scales, and claws. The rim of the plate features wave and dot-line patterns. The interior and exterior walls feature bird head-shaped patterns, and the exterior bottom is inscribed with the characters “Ju Hou Jia” in red. A total of nine such flat plates were unearthed from this tomb. The funeral inventory list refers to them as “lacquer painted flat plates,” likely used for serving food during banquets.

From the artifacts unearthed at the Mawangdui Han Tombs, we learn that the dining utensils of the early Han Dynasty were quite abundant. The concepts of “banquet” and “dining separately” that we speak of today originated from the dining etiquette of that time. During the Han Dynasty, banquets were held on mats, with seating arranged according to rank. Guests and hosts sat on the ground in order of their status, with food tables placed in front of them. Various dining utensils were arranged on the tables, and the abundance and simplicity of the food varied according to the rank of the diners. Large vessels such as tripod cauldrons (ding), wine vessels (zhong), wine vessels (zhong), and pots were placed on the mats outside the seating area.

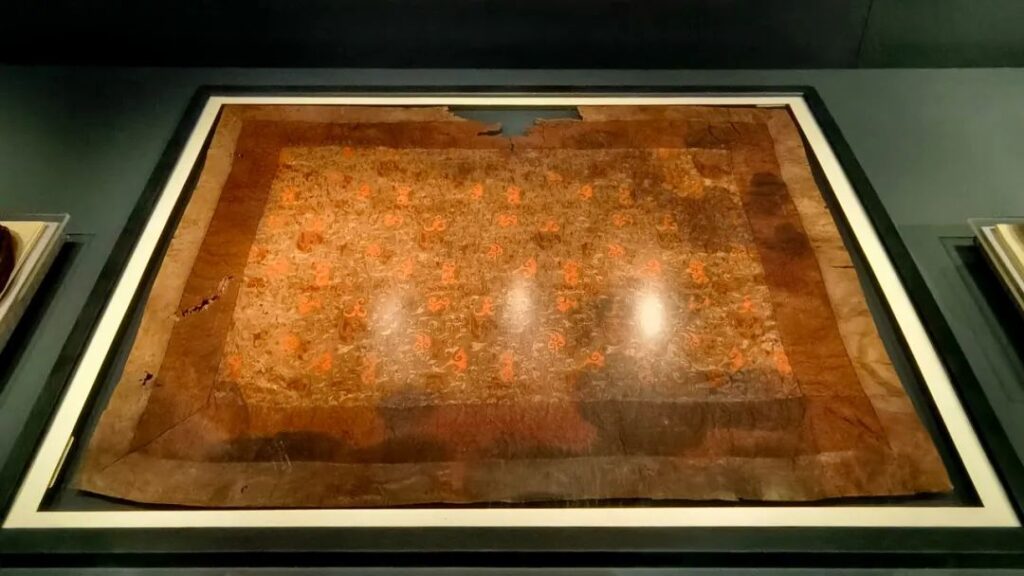

The Mawangdui Han Tombs have unearthed a large number of exquisite silk fabrics in a wide range of categories. These silk fabrics vary in texture and weaving structure, including silk tabby (juan), silk gauze (sha), silk damask (ling), silk twill (qi), brocade (jin), silk netting (luo), and silk ribbons (tao). The hundreds of excavated garments feature decorative techniques such as dyeing, printing, painting, and embroidery. The vibrant colors and exquisite craftsmanship testify to the outstanding achievements of the textile industry in the early Han Dynasty.

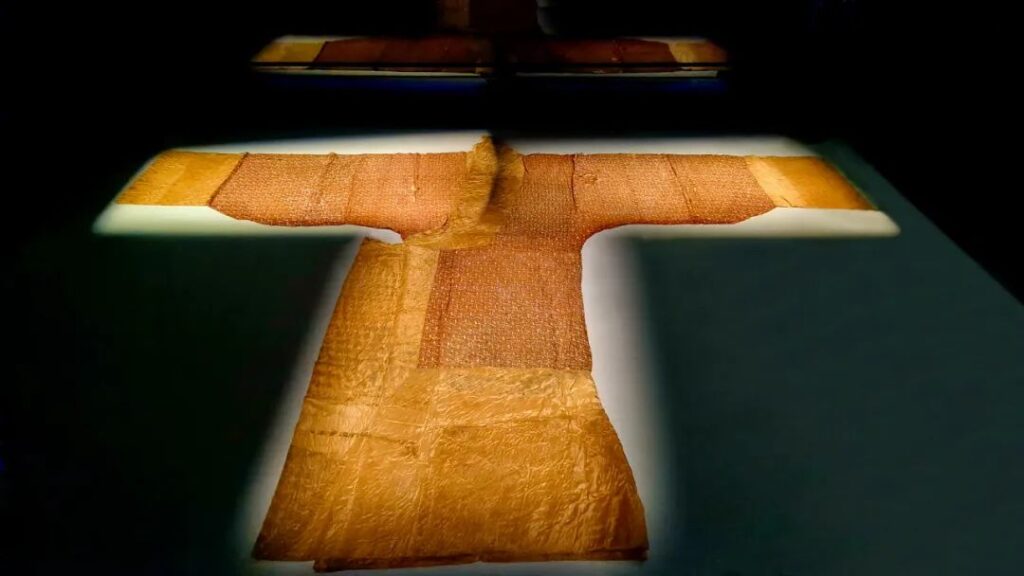

The plain gauze short-sleeved robe (quju su sha ru yi) is a pinnacle of textile craftsmanship from the Western Han period. The warp and weft threads of the garment are extremely fine, truly as thin as a cicada’s wing, with the entire garment weighing less than 50 grams and remaining well-preserved for over two thousand years. The plain gauze zen robe has a crossed collar, with the curved hem folded from left to right, and the garment is relatively long. The plain gauze zen robe is worn as the outermost layer, and when worn, the sleeves float like clouds, appearing and disappearing.

The vermilion lozenge-patterned silk gauze robe (zhu hong ling wen luo si mian pao) has an upper garment connected to a lower skirt, with a crossed collar and a curved hem folded from left to right to the right side of the body. This style was widely popular among aristocratic women in the early Western Han Dynasty. The vermilion lozenge-patterned silk gauze fabric is a single-color, dark-patterned, twisted warp silk fabric. It is speculated that the production process of this fabric is intricate and complex. The plain gauze short-sleeved robe and the vermilion lozenge-patterned silk gauze robe represent the highest level of sericulture, silk reeling, and weaving craftsmanship in the early Han Dynasty.

The yellow gauze printed and painted silk robe (huang sha di yin hua fu cai si mian pao) is a garment made by combining printing and painting techniques. This style of silk robe was likely a glamorous fashion for aristocratic women in the Han Dynasty. The silk robe has a fresh and elegant appearance, as well as a luxurious and exquisite look. Its emergence confirms the reliability of the records in literature regarding “painted clothes” and “painted patterns,” reflecting the superb printing and dyeing processing techniques of the Han Dynasty.

The Mawangdui Han Tombs have unearthed a large number of musical instruments, gaming sets, musical figurines, and silk paintings depicting banquet scenes. These cultural relics fully reflect the grandeur of the ancient aristocratic lifestyle, and the banquet entertainment of the Marquis of Dai’s family was probably a common occurrence. The music-playing figurines, ranging from 32.5 to 38 centimeters in height, can be considered the earliest small orchestra model currently known in China.

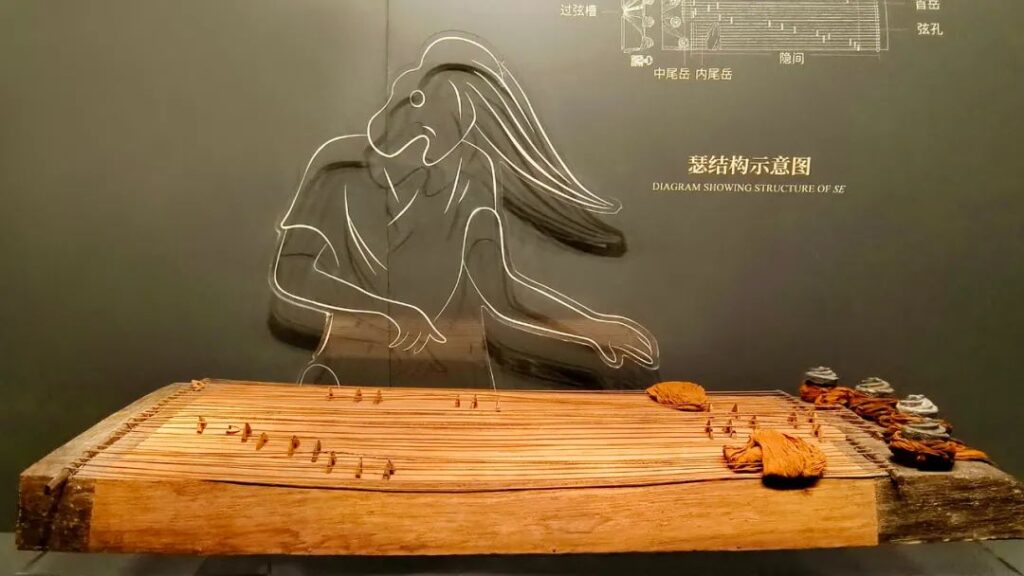

The tomb of Xin Zhui unearthed a twenty-five-stringed se zither, a twenty-two-pipe yu, and a set of yu pitch pipes, as well as models of three musical instruments: bells, chimes, and zhu, attached to wooden figurines. These are the first Western Han musical instrument artifacts to be discovered. In addition, the funeral inventory list of Li Xi’s tomb records many names of songs, dances, and musical instruments.

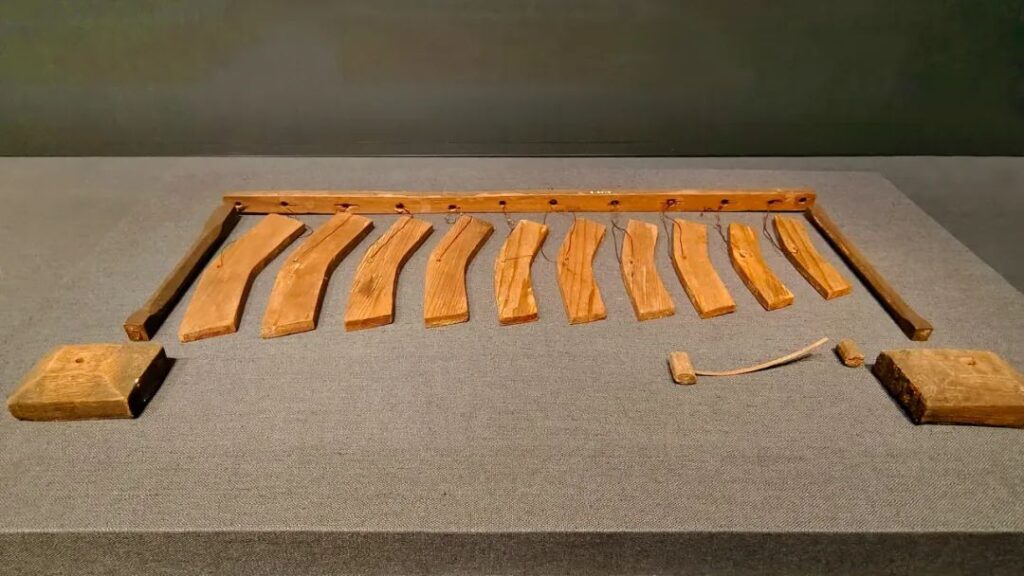

The twenty-five-stringed se zither, unearthed from Xin Zhui’s tomb, has complete components and clear bridge positions. The 25 silk strings are attached to wooden tuning pegs, with a movable tuning post under each string. There are resonance windows at both ends of the bottom. This instrument is the most complete ancient se zither currently in existence in China, providing extremely valuable physical materials for studying the history of ancient music and the performance methods of Han Dynasty musical instruments.

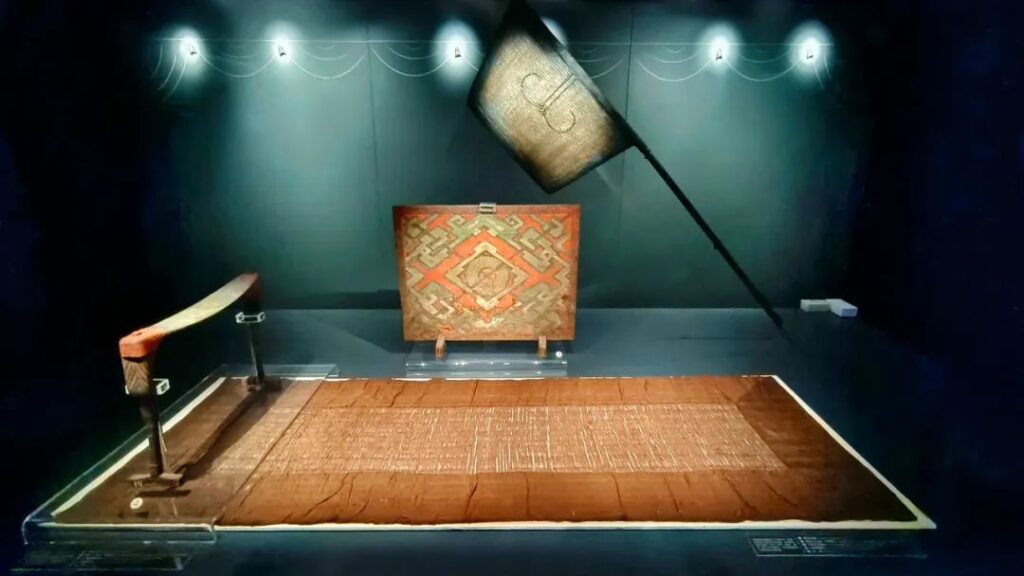

The “bo” set is an elegant intellectual game set unearthed from Li Xi’s tomb. The game of “bo” was already popular in the pre-Qin period and was especially prevalent in the Han Dynasty, enjoyed by everyone from the emperor and officials to the common people. This set includes 1 game board, 12 large pieces, 20 small pieces, 42 counting sticks, an 18-sided die, 1 carving knife, and 1 scraping knife, all stored in a specially made lacquer box.

The Mawangdui Han Tombs are the richest in terms of the unearthed wooden figurines from the Western Han period, with a total of 266 various wooden figurines excavated. These wooden figurines represent the identities of household officials such as the “jia cheng,” the tomb owner’s personal maids, as well as singing, dancing, and music-playing figurines. Therefore, it can be seen that the Han Dynasty aristocrats spared no effort in ensuring they could continue to enjoy their previous lifestyle in the afterlife.

In addition to the high-level figurines mentioned above, the Mawangdui Han Tombs also unearthed hundreds of ordinary servant figurines. They wear crossed-collar, right-lapel, wide-sleeved, and curved-hem long robes, with the robe hems decorated with black-background red-patterned woven brocade, and the robe surfaces featuring lozenge and cloud patterns. Their hands are folded inside their sleeves. The male figurines have flat heads, while the female figurines have hair buns on the top of their heads, with a bamboo stick inserted into each bun.

Long-handled bamboo fans, cloud and dragon patterned lacquer screens, cloud-patterned lacquer tables, and reed mats. Since the pre-Qin period, the custom of sitting and living on the ground was still followed in the Han Dynasty. When aristocrats and elders sat cross-legged, they often had a small table, with their knees tucked under the table and their elbows resting on top. Maids would sit cross-legged beside them, holding bamboo fans, and low screens were placed according to etiquette. This scene reflects the main room furnishings of the tomb owner during their lifetime.

The Li family lived during the Wen-Jing period, a time of great prosperity. They were wealthy and had a collection of rare and exotic treasures from various places, including ivory, jade, pearls, rhinoceros horns, and tortoiseshell. They led a life surrounded by servants and endless singing and dancing. However, the Mawangdui Han Tombs rarely contained precious metal objects such as gold or bronze, which may be related to Emperor Wen of Han’s advocacy of thrift burials. Items such as the Ying cheng (a type of scale), gold cakes, copper coins, rhinoceros horns, ivory, and jade bi (ceremonial discs) were all replaced with pottery and wooden replicas.

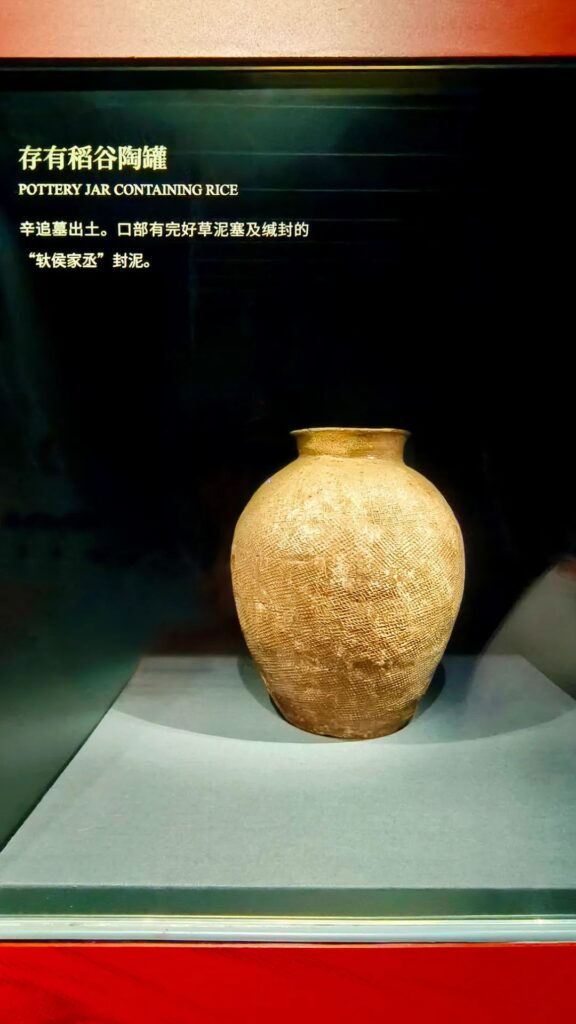

Although no porcelain was unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tombs, a large number of pottery items were found. Both the variety and the pottery-making techniques far surpassed those of the Warring States period. Moreover, the hard pottery with printed patterns had brown and yellow-green glazes applied, which was an important step in the transition from pottery to porcelain. A lacquer-painted pottery tripod cauldron, used for cooking and serving food, still contained chicken bones when it was excavated.

The Mawangdui Han Tombs also unearthed a large number of bamboo containers and boxes used for storing food, silk, traditional Chinese medicine, spices, and clothing. The bamboo weaving was exquisite. The excavated silk books and bamboo slips were copies of literature from the Warring States period to the early Han Dynasty, covering various fields such as philosophy, politics, military affairs, astronomy, geography, medicine, history, and art.

In the pottery jars and bamboo baskets of Xin Zhui’s tomb, various grains, vegetable seeds, and fruits were found, most of which were very well-preserved upon excavation. There were several dozen varieties, including rice, wheat, barley, jujubes, plums, and bayberries, reflecting the prosperity of agriculture in southern China at that time. The mouths of the pottery jars had intact sealing clay inscribed with “Liang Hou Jia Cheng” (a title of an official).

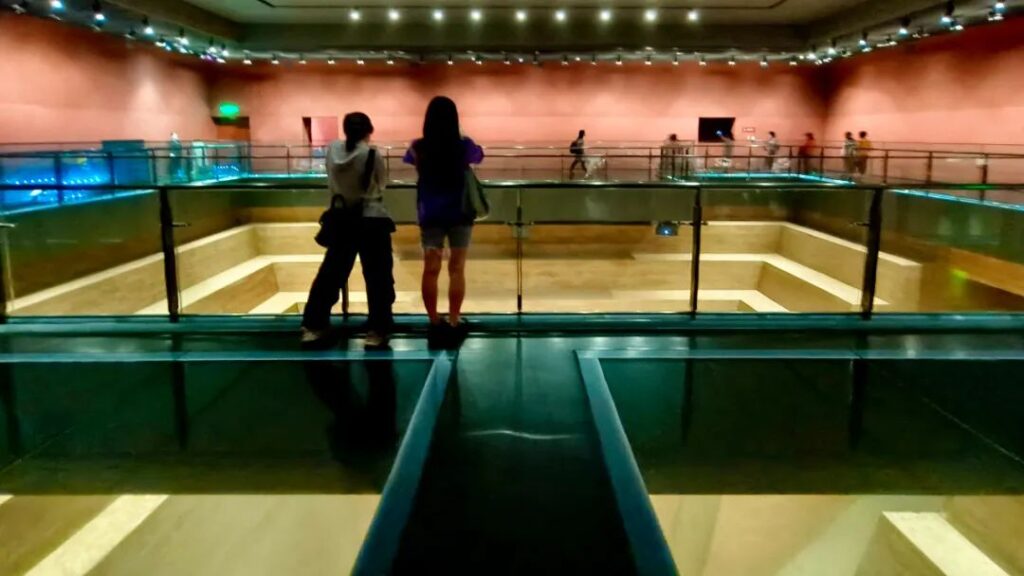

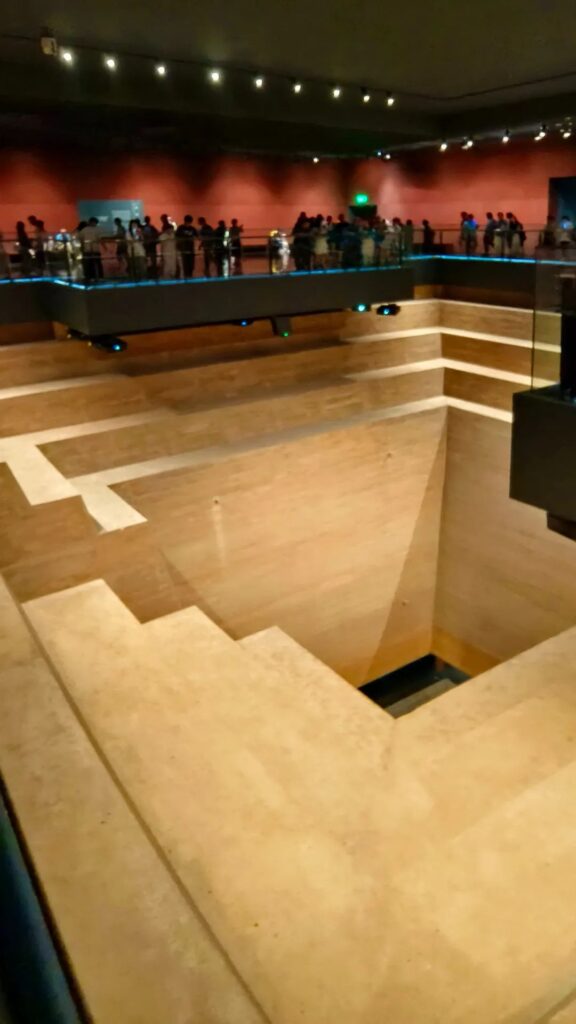

After visiting the Han tomb exhibits, I arrived at the well chamber exhibition hall. The museum designed the approximately 18-meter-high space from the first to the third floor to be the same proportions as Xin Zhui’s tomb chamber. Looking down from above, one can vaguely see the coffin of Xin Zhui’s wife. This demonstrates the enormous earthworks involved in the Mawangdui Han Tombs, and only aristocrats had the ability to construct such luxurious tombs after their deaths.

Going down to the first floor and entering the outer coffin chamber exhibition hall, one can see that the coffin structure of Xin Zhui’s tomb is very complex. The tomb structure is grand and intricate, with the outer coffin chamber constructed at the bottom of the tomb pit, consisting of three outer coffins, three inner coffins, and cushioning wood. The huge outer coffin chamber is placed on three large pillow timbers, and four nested wooden coffins are placed inside the chamber. The wooden outer coffin structure of Xin Zhui’s tomb inherited the style of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, made of 70 thick cedar planks.

Inside a glass-covered large coffin, I saw the remains of Xin Zhui’s wife. There lay a woman about 1.5 meters tall, covered with a white woven fabric, and her entire body appeared to be intact. Although there was some distance and a glass cover, it was still generally clear to see. The exhibition hall constantly reminded visitors that photography was not allowed. Fortunately, I encountered the Mawangdui Han Tomb exhibition in Chengdu a few years ago, so I’m attaching photos taken in Chengdu here.

It is said that Xin Zhui died in 186 BC at the age of about 50, more than two thousand years ago. When Xin Zhui’s body was unearthed, it was moist all over, with intact skin coverage, remaining hair, and elasticity in the subcutaneous tissues. In 2002, the Hunan Provincial Museum successfully restored Xin Zhui’s head portrait. In 2003, the museum used polymer materials to restore Xin Zhui’s original appearance.

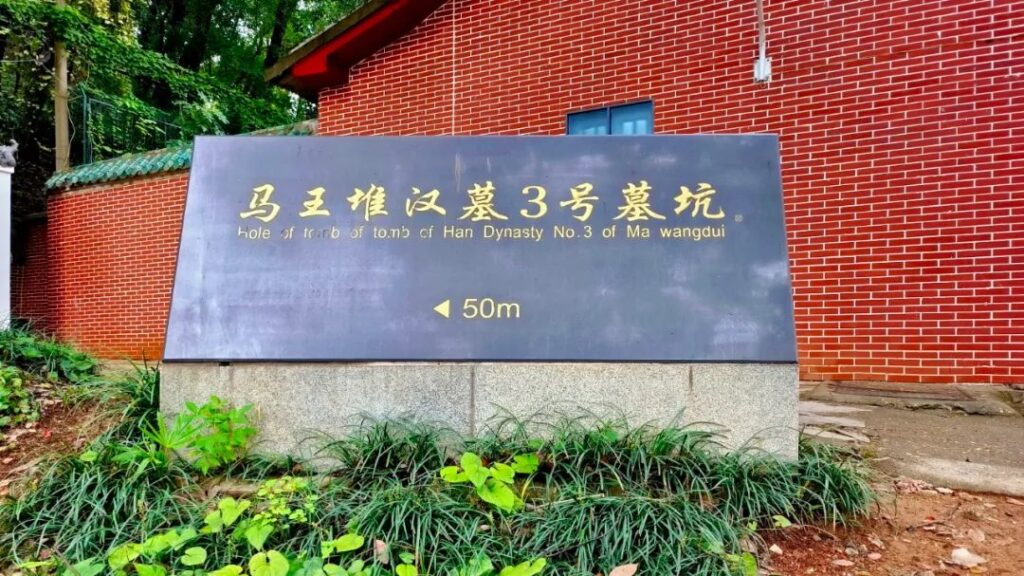

Leaving the Hunan Provincial Museum, I arrived at the Mawangdui Han Tomb site inside the Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital. In the past, two strange mounds stood here, protruding from the fields like a horse’s saddle. The locals called them “Mawangdui” (Horse King Mounds). In the winter of 1951, archaeologists discovered the ancient Mawangdui tombs during a survey. In 1956, the Mawangdui Han Tombs were announced as the first batch of cultural relic protection units in Hunan Province.

At the end of 1971, the Hunan Provincial Military Region’s 366 Hospital was digging an air-raid shelter on the eastern side of the Mawangdui mounds. During construction, they often encountered cave-ins and flammable gas. Archaeologists from the Hunan Provincial Museum rushed to the scene and discovered that the tomb pits of the Han Dynasty ancient tombs had been excavated. They then reported to the State Council and applied for an official excavation of the Mawangdui Han Tombs. Subsequently, the name “Mawangdui” was forever imprinted in the history of Chinese archaeology.

After excavating Tombs No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 at Mawangdui, archaeologists confirmed that these were the family tombs of Li Cang, the Marquis of Dai and the chancellor of the Changsha Kingdom during the Western Han Dynasty, his wife, and son. Later, Tombs No. 1 and No. 2 were backfilled, and only Tomb No. 3 was preserved with a temporary exhibition hall built. Nowadays, the surrounding fields have been transformed into tall buildings, and the once-mysterious Mawangdui has been submerged in the bustling urban area.