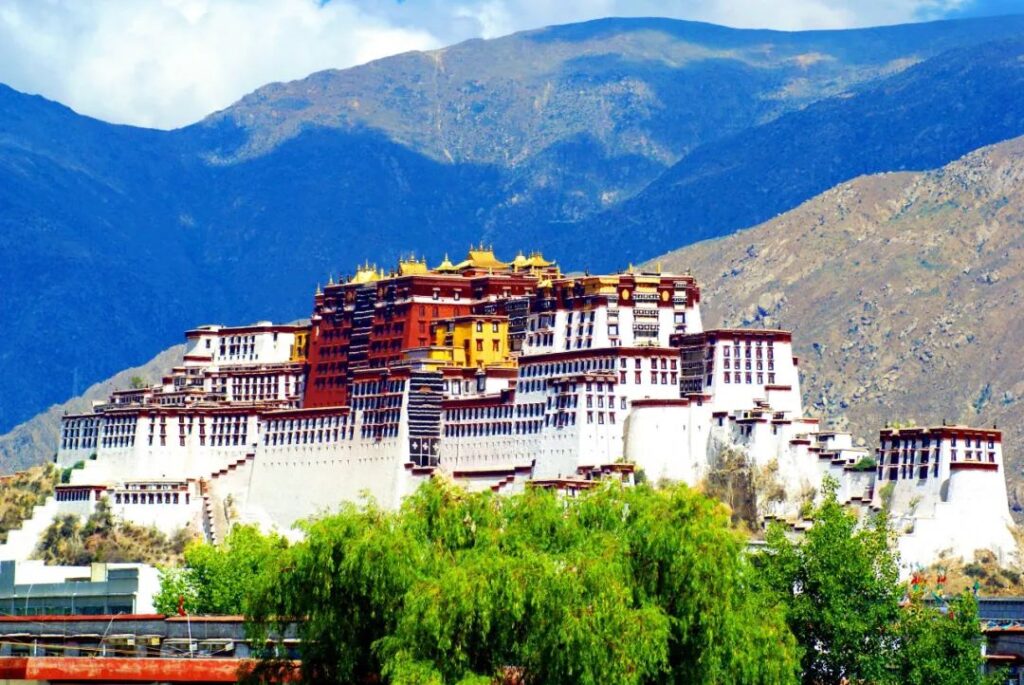

As you approach the holy city of Lhasa, even from dozens of miles away, the majestic Potala Palace perched atop the Red Hill in the heart of the city comes into view, thanks to the crystal-clear air unique to the high plateau. The grand and magnificent Potala Palace is an architectural complex that combines a palace, temples, and stupas, and it is also the highest ancient palace in the world.

According to legend, Songtsän Gampo, the king of Tubo, was a devout Buddhist. After moving his capital to Lhasa, he often chanted sutras and prayed on the Red Hill near the city. During the Zhenguan period of the Tang Dynasty, in order to marry Princess Wencheng of the Tang court, Songtsän Gampo specifically built a palace with 999 rooms on the Red Hill. Together with the meditation rooms on the hill, there were a total of 1,000 rooms, and the palace was named Potala Palace.

“Potala” is a transliteration from Sanskrit, originally referring to the abode of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. It is said that both Songtsän Gampo and the Dalai Lamas are incarnations of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, and the place where they reside is called “Potala Palace” by the Tibetan people. In the hearts of Tibetans, Potala Palace has long transcended the realm of architecture and entered the spiritual domain of the people. Many Tibetans prostrate themselves to worship the Potala Palace.

It is said that after the fall of the Tubo Dynasty, the Potala Palace was struck by lightning and destroyed during the war, leaving only the Dharma King Cave built by Songtsän Gampo and his personal Buddha Hall. During the Shunzhi period of the Qing Dynasty, the Fifth Dalai Lama unified Tibet and, after being conferred the title by the Qing court, began to rebuild the Potala Palace. Subsequent Dalai Lamas continued to expand the palace, eventually forming the scale we see today.

Standing in the Potala Palace Square and looking up, the Potala Palace complex is built along the mountain, with overlapping buildings and towering halls, exuding a majestic atmosphere. The tall and thick granite walls, the white straw walls piled up like strange willows, the golden and glittering palace roofs, and especially the huge gilded treasure vases on the roofs, all radiate golden light under the brilliant sunshine, creating a grand and awe-inspiring beauty that is truly shocking.

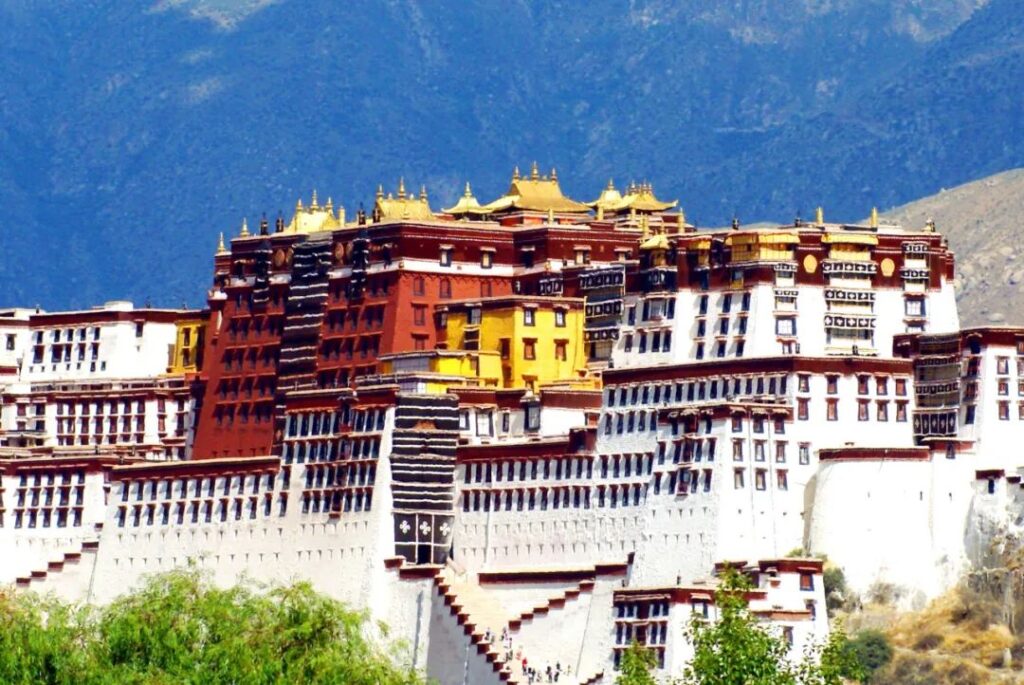

The exterior walls of the Potala Palace are painted in bright white, yellow, and red, colors closely associated with Tibetan Buddhism: white symbolizes tranquility and peace, yellow represents perfection, and red signifies authority. The striking contrast of colors makes the entire Potala Palace complex appear distinct, well-structured, and enchanting, reflecting the charming characteristics of ancient Tibetan architecture.

The Potala Palace can be divided into the White Palace and the Red Palace based on the colors of the exterior walls. The White Palace has a compact structure, forming a U-shape that runs through the main body of the Potala Palace from east to west. The Red Palace, on the other hand, is densely packed and sits above the concave part of the White Palace, making the entire White Palace resemble two hands holding a pagoda. The golden roofs on top of the Red Palace glitter in the sunlight, seemingly displaying their supremacy.

From the foot of the mountain to the palace gate at the top, there is a height difference of about 100 meters. However, I spent 30 minutes on this stretch of road. If this were on the mainland, one could easily climb from the foot of the mountain to the top without much effort. However, the altitude of Lhasa is 3,650 meters, and the altitude of the Potala Palace is 3,767 meters. Everyone who climbs the Potala Palace is gasping for breath and slowly ascending with difficult steps.

On the outer side of the mountain path, there are tall brima walls. The brima wall is a crystallization of the wisdom of the Tibetan people. It can reduce the weight of the top of the wall and achieve visually pleasing effects. When building the wall, a layer of bundled brima branches is laid first, followed by a layer of compacted clay. This process is repeated until the wall is completed. The top of the wall is then waterproofed, and the surface is painted with vermilion pigment.

The Potala Palace is built on the natural terraces of the Red Hill, reaching the top of the mountain. The entire palace is about 200 meters high, with 13 stories on the exterior but only 9 stories in reality. Since it is built on the mountainside and the large area of stone walls stands like cliffs, the entire building appears majestic, as if it has become one with the mountain. The palace structure is entirely supported by wooden beams, and the walls are built with square stones, with a thickness of over 1 meter and up to 5 meters at the thickest points.

Walking along the Z-shaped brima wall, the wall extends all the way to the entrance of the White Palace. On the mountain path, I saw devout Tibetans accompanying tourists to the Potala Palace. Only after entering the Potala Palace did I realize that Tibetans and tourists follow two different routes. There are some places where Tibetans can worship, but tourists are not allowed to enter.

The first part of the Potala Palace that visitors enter is the White Palace, named for its white exterior walls. This is where the Dalai Lama lives and resides, but due to privacy or other reasons, visitors can only tour certain areas. Upon entering the White Palace and crossing the threshold of a large hall, there are huge murals painted on both sides of the corridor. The murals exude a sense of might and majesty, and upon closer inspection, they depict the four great guardian kings of the Buddhist realm.

On the top floor is the Sunshine Hall, the Dalai Lama’s bedchamber, named for its roof that can be opened to let in sunlight. The Sunshine Hall is divided into eastern and western parts. The Western Sunshine Hall is the original hall, while the Eastern Sunshine Hall is a later imitation. The two have similar layouts and served as the bedchambers of the 13th and 14th Dalai Lamas, respectively, as well as where they handled political affairs. The halls contain scripture rooms, worship rooms, study rooms, and bedrooms.

The Red Palace, located in the central part of the Potala Palace, has red exterior walls. The palace adopts a mandala layout, with many scripture halls and Buddha halls built around the stupas of the Dalai Lamas after their passing, integrating with the White Palace. Other notable features inside the palace include the eight stupas of the 5th Dalai Lama and the 7th to 13th Dalai Lamas, with the stupa of the 5th Dalai Lama being the largest.

The stupas are the burial places of the Dalai Lamas throughout history. Not only are the stupas covered in pure gold or silver, but they also contain various treasures. The most amazing treasure is a pearl enshrined in the stupa of the 5th Dalai Lama, said to have formed inside an elephant’s brain. In Tibetan, this stupa is called “Zanmu Lingqian Ji,” meaning its value is equivalent to half of the world.

The Potala Palace is not only stunning on the outside but also houses a large number of artworks and rare cultural relics. The most precious among them are the vast collections of scriptures, some written in gold ink, some in silver ink, and some with gold and silver embossed characters. The Potala Palace also holds a complete collection of over 100 boxes of ancient Indian palm-leaf scriptures, which have long been lost in India.

The Potala Palace contains historical relics such as the imperial edicts, seals, golden books, and jade books bestowed by the emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties to Tibetan officials. It also houses a large number of precious cultural relics, including scriptures, medical books, historical books, literary works, as well as various Buddha statues, thangkas, and ritual implements. The Potala Palace is both a museum of history and a palace of art, and it is a symbol of Lhasa and the entire Tibet.

In the design and construction of the Potala Palace, based on the patterns of sunlight in the plateau region, the wall foundations were built wide and solid, with a network of underground passages and ventilation openings beneath them. The interior has columns, brackets, beams, rafters, and other components forming the support structure. The roof uses durable and wear-resistant aga soil, and the ceilings inside all have skylights for lighting and air regulation.

The interior of the Potala Palace is dimly lit, with the distinctive smell of yak butter permeating the air. Under the flickering light of the yak butter lamps, many Tibetans continuously add butter to the lamp troughs, each with a solemn expression on their face. My gaze lingers on a Tibetan mother standing in front of the butter lamps, carefully pouring butter, her weathered face filled with devotion.

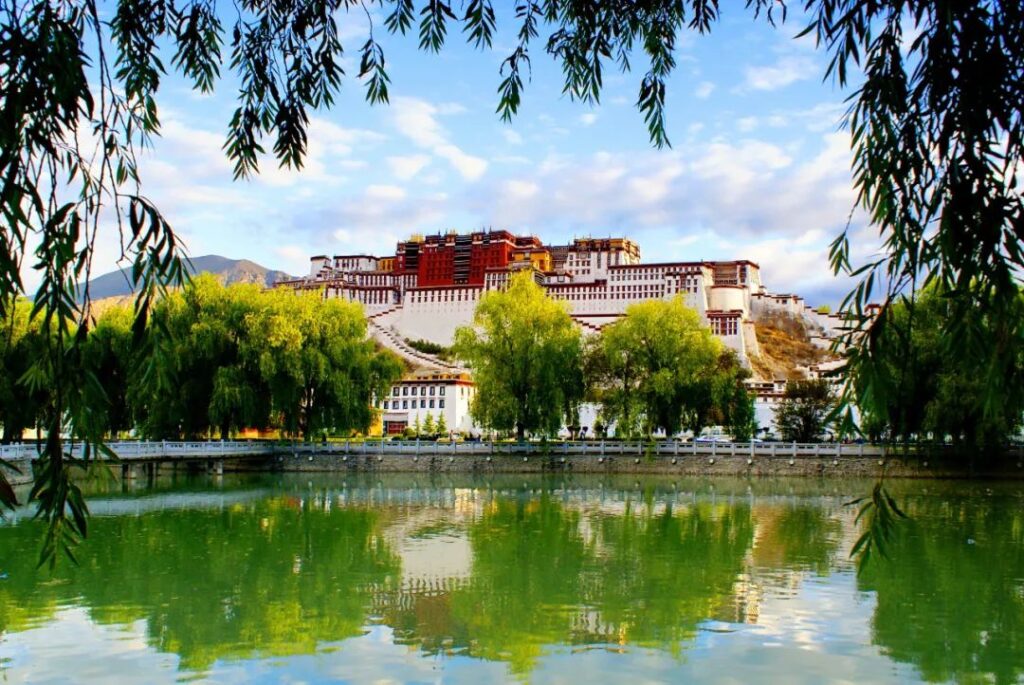

In front of the Potala Palace, within the palace walls, there are many white Tibetan-style buildings called the “Snow City.” This area houses the offices of the former Tibetan Kashag government, including the court, the scripture printing house, the Tibetan army headquarters, and various workshops, stables, water supply facilities, warehouses, military camps, prisons, and other auxiliary facilities.

Behind the Potala Palace is a garden complex centered around the Dragon King Pond, known as “Lingka,” which serves as the back garden of the Potala Palace. It is said that when the 5th Dalai Lama rebuilt the Potala Palace, soil was taken from here, forming a deep pond. Later, the 6th Dalai Lama built a three-story octagonal glazed pavilion in the pond to enshrine the Dragon King, hence the name Dragon King Pond.

When visiting the Potala Palace, one must observe all the taboos of Tibetan Buddhism. After entering the palace, visitors must remove their hats, refrain from taking photos, and avoid stepping on thresholds. All visitors must complete the tour within 1 hour, so stopping at any location inside the palace is not allowed. After the tour, visitors exit from the west gate of the Potala Palace and can walk down the back hill slope to the main entrance of the Potala Palace.

After the tour, watching the Tibetans walk past the prayer wheels, I can’t help but recall what Lin Yutang once said: “Religion is a kind of divine feeling, a sense of life, and a feeling of the cosmic mystery, solemnity, and grandeur. It is the exploration of the safety of life, thus satisfying the deepest spiritual instincts of human beings.” The Tibetans’ unwavering devotion to their faith is truly admirable and deeply moving.