The Shenyang Imperial Palace is a magnificent complex of Qing Dynasty palaces that embodies the distinctive Manchu style. It served as the imperial palace of the Shengjing region before the Qing Dynasty entered the Shanhai Pass and later became the secondary palace after the dynasty’s relocation.

This palace is also the birthplace of China’s last feudal dynasty, bearing witness to the rise, zenith, and fall of the Qing Empire. It is one of the only two remaining imperial palaces in China, where every brick, tile, grass, and tree seems to whisper the yearning of the Qing Dynasty to conquer the Central Plains from its humble beginnings as the Later Jin.

Nurhaci established the Later Jin here, and Emperor Huang Taiji ascended the throne, becoming the first emperor of the Qing Dynasty.

The Qing Empire, which emerged from Liaodong, laid its foundation in this very place and evolved from a regional power to a dynasty that ruled over China. After the Qing court moved its capital to Beijing, the Shenyang Imperial Palace continued to be protected, repaired, and expanded as a secondary palace and a temporary residence for emperors during their eastern tours to pay respects at the imperial tombs.

On the Ming-Qing Street in front of the palace, the houses on both sides still retain the Qing-era style, with red walls, yellow roofs, green bricks, and upturned eaves. These buildings seem to recount the story of how the Manchu ancestors transformed from a nomadic tribe into a feudal empire.

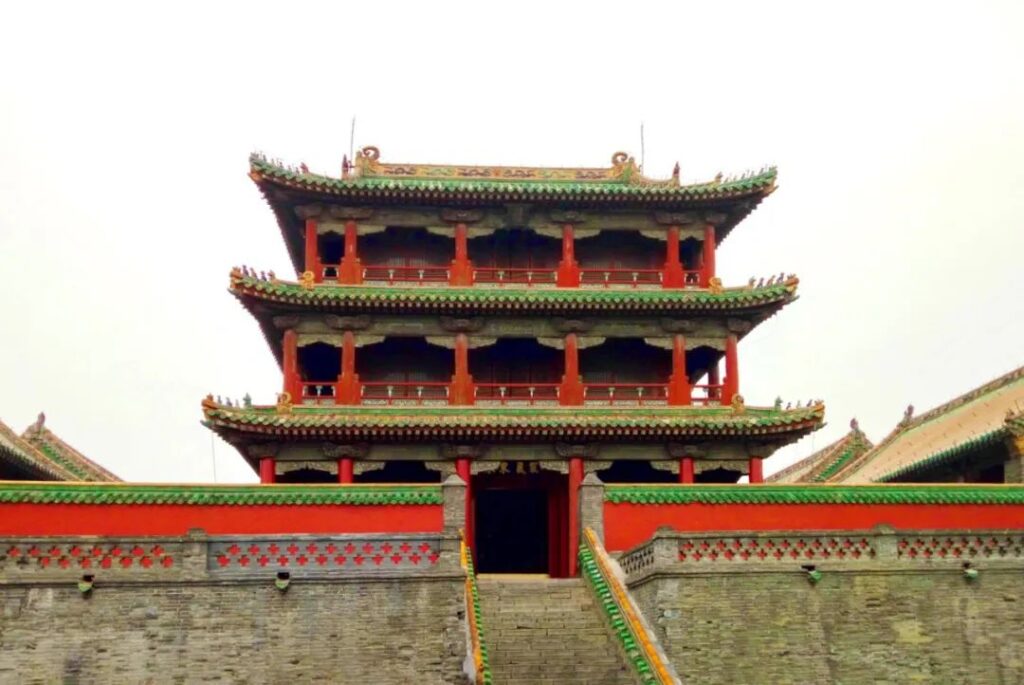

As I stand before the main gate of the palace, it does not appear as imposing and solemn as I had imagined. Instead, it is majestic and magnificent, with intricate carvings and paintings, blending harmoniously with the entire palace complex. The Daqing Gate, the main entrance to the palace, is where civil and military officials would await the emperor’s arrival before the imperial court sessions.

The roof of the Daqing Gate is fully covered with glazed tiles and adorned with green-trimmed edges, preserving the traditional concept of yellow as the noblest color while reflecting the Manchus’ affinity for mountains and forests. At the top of the gate’s gable walls, four protruding ridges on the north and south sides are inlaid with colorful glazed tiles on three sides, depicting patterns of surging waves, dragons, and various auspicious animals.

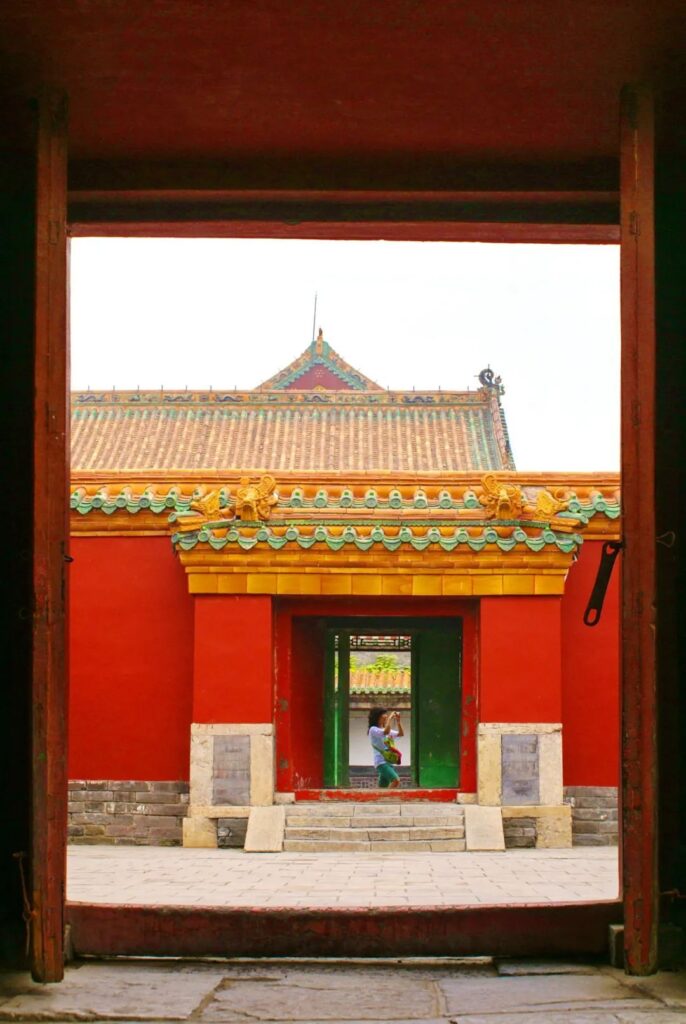

Upon entering the palace gate, the East Yemen and the screen wall come into view. Yemen is an elegant term for side gates or convenient entrances. Although the East Yemen is an inconspicuous side gate, it is still a side entrance to the imperial palace. It appears exquisite, grandiose, and exudes the opulent atmosphere unique to a royal residence.

Directly facing the palace gate is the Chongzheng Hall, commonly known as the “Jinluan Hall.” It is the most important hall in the palace, featuring a five-bay structure with a double-eaved hip roof and front and rear corridors. In front of the hall lies a spacious red-tiled platform, and the roof is covered with yellow glazed tiles. Behind the hall is the Phoenix Building, the tallest structure in the palace, and the imperial bedchambers on the elevated platform.

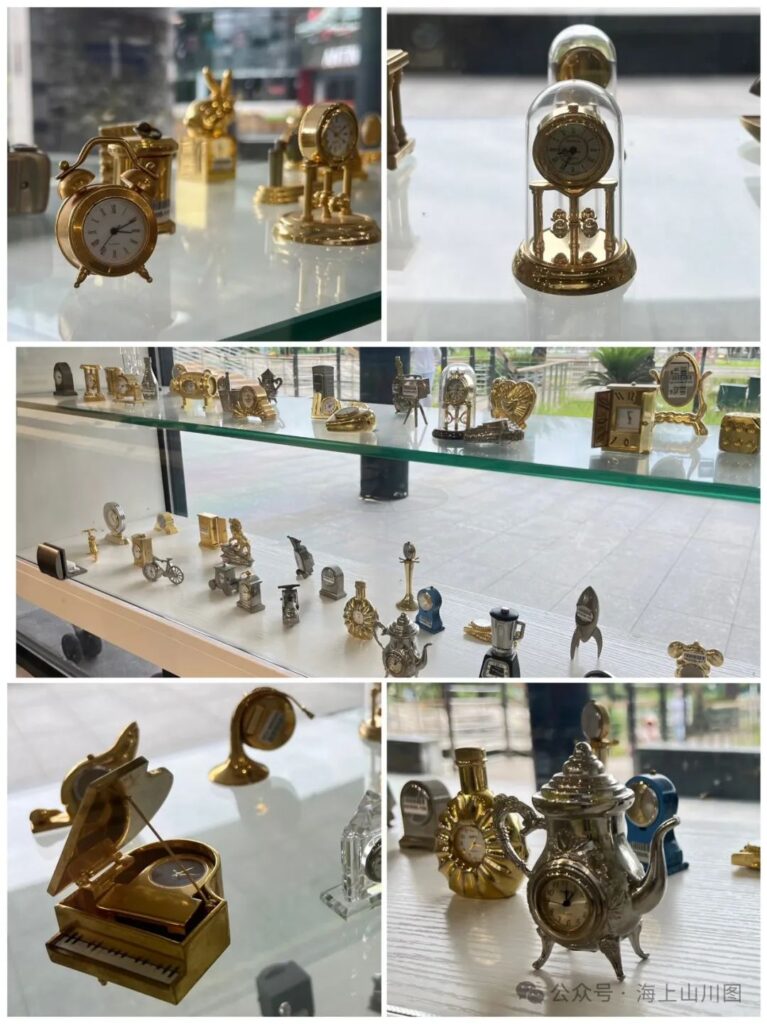

On the platform in front of the Chongzheng Hall, a sundial and a standard measuring vessel are placed. The sundial, also called a gnomon, is an ancient timekeeping device that utilizes the shadow cast by a pointer on a dial to indicate time. The standard measuring vessel represents the ancient standard of measurement. The sundial here was installed during the Qianlong era and, together with the measuring vessel, symbolizes the longevity of the dynasty and the unity of the country.

Peering into the hall, the vast, hollow interior is supported by tall columns. The colors have faded, the freshness has diminished, and everything appears worn and dilapidated. Inside the hall, a gilded throne exudes the imperial aura with its opulence. The emperor often received homage from his subjects here, met with foreign envoys and officials, and handled military and political affairs.

The Dazheng Hall, built during the reign of Nurhaci, is the most solemn and sacred place in the palace. This octagonal, double-eaved pavilion-style building features yellow tiles, green eaves, gold dragon-coiled columns, and lavish decorations. The roof is fully covered with yellow glazed tiles, trimmed with green edges, and topped with a central wheel, flame, and pearl. Eight iron chains connect the top to the surrounding warriors, and two golden dragons coil around the front columns.

The Dazheng Hall is surrounded by stone railings adorned with carved lions and beasts, exuding an air of solemnity. This hall gives the impression of a miniature version of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. Inside, the hall features a Sanskrit-style ceiling, dragon-themed caisson, and exquisite carvings and paintings, showcasing artistic flair. The hall also contains a throne, screen, incense burner, crane-shaped candlesticks, and other furnishings.

The Dazheng Hall served as the venue for the Qing emperors’ major ceremonies and important events, such as the enthronement of a new emperor, the issuance of imperial edicts, the announcement of military expeditions, and the welcoming of triumphant generals. In front of the Dazheng Hall, ten square flag pavilions are arranged, modeled after the tents of the Khan and the Eight Banner princes during military campaigns and hunting expeditions. These pavilions are also known as the Ten King Pavilions.

The architectural layout of the Dazheng Hall and the Ten King Pavilions reflects the Qing Dynasty’s military and political system, which centered on the Eight Banners. This layout is unique in the history of ancient Chinese palace architecture. Whenever a significant event occurred, the emperor would sit in the Dazheng Hall, while the kings and princes of the Eight Banners would occupy the pavilions in front of the hall, forming a joint office for the monarch and his ministers to handle state affairs.

Both the Dazheng Hall and the Ten King Pavilions are embodiments of tents, with the Dazheng Hall being larger in scale and more lavishly decorated. Tents are mobile and can be relocated, while pavilions are fixed in place, reflecting the development of Manchu culture. Centuries have passed, and those kings and princes have long since passed away, leaving behind only these empty buildings.

Located north of the Chongzheng Hall, the Phoenix Building, originally named “Xiangfeng Building,” is the gate tower of the Qingning Palace’s inner courtyard. The three-story building has a hip-and-gable roof and measures three bays in width and depth. This was once the place where the emperors of the Great Jin Dynasty discussed military and political affairs and held banquets. After the Qing Dynasty entered the Shanhai Pass, it was used to store the historical records, jade tablets, imperial portraits, and seals of past dynasties.

The Qingning Palace was the residence of Emperor Taizong of the Qing Dynasty, Huang Taiji, and his empress, Borjigit. Upon entering the Qingning Palace, one notices that it differs from other rooms, with three sides featuring a kang (a heated brick bed). Due to its shape resembling the character “wan” (万), it is also called the “Wan-shaped Kang.” As it is enclosed on all four sides, the emperor named it the “Pocket Room.”

The Qingning Palace reflects the Manchu people’s lifestyle and aesthetic customs in its courtyard layout, floor plan, interior space division and connection, as well as its exterior appearance and decorative features. However, compared to ordinary Manchu residences, it is larger in scale, uses more exquisite materials, boasts more lavish decorations, and showcases more refined craftsmanship, embodying the characteristics of imperial architecture.

Inside the Qingning Palace, there are two large cauldrons used for sacrificial rituals. The Manchu people believe in Shamanism, and the Shaman ritual process is both solemn and mysterious, often referred to as “jumping the great god.” During the ritual, hot wine is poured into a pig’s ear. If the ear twitches, it indicates that the deities have accepted the offering. If it remains still, it means the deities are dissatisfied, and the ritual cannot proceed.

The Shenyang Imperial Palace, being the imperial palace of the Qing Dynasty before it entered the Central Plains, records the rise of a nation. As the most complete imperial palace complex in China after the Forbidden City in Beijing, it inherits the traditions of ancient architecture and possesses high artistic value.

Although the architectural scale and grandeur of the Shenyang Imperial Palace may appear slightly inferior to the Forbidden City in Beijing, its architectural style is exquisite and compact. The Shenyang Imperial Palace is an artistic treasure of the Chinese nation, a historical heritage of the convergence and integration of Manchu and Han cultures, a crystallization of the wisdom of the Manchu and Han people, and an embodiment of the profound and extensive Chinese culture.

Walking along the dark red walls and strolling through the palace complex, one can see the fierce bronze lions, golden door studs, ancient memorial archways, and long palace walls, all exuding an air of majesty and elegance. The stone bricks on the ground no longer bear the traces of the bustling traffic of bygone days. The red walls openly expose white scars.

This ancient, splendid culture and magnificent architectural art have cleansed and shocked my soul. As I listen to my own faint footsteps leaving the palace and look back at this complex that has weathered hundreds of years of wind, frost, snow, and rain, it seems as if a fragmented piece of history is quietly fading away.