The Shanghai History Museum, also known as the Shanghai Revolution History Museum, is officially called the “Shanghai History Museum (Shanghai Revolution History Museum)” in formal designations.

This dual naming stems from the fact that the current museum is the result of a merger between two earlier institutions – the Shanghai History Museum and the Shanghai Revolution History Museum.

Located at 325 West Nanjing Road, the Shanghai History Museum sits adjacent to the western side of People’s Park, at the intersection of West Nanjing Road and North Huangpi Road. For me, this building is quite familiar. Before its transformation into the Shanghai History Museum, it served as the home of the Shanghai Art Museum for many years, where I frequently visited art exhibitions. Since 1996, it has hosted seven biennales.

Following the World Expo, the Shanghai Art Museum relocated to the China Art Palace, and the biennale moved to the Museum of Contemporary Art. This historic building underwent renovation and reopened as the Shanghai History Museum in November 2017.

The building itself, constructed in 1933, was originally the Race Club of the old Shanghai Race Course, exemplifying the 1930s English architectural style. Despite being surrounded by modern skyscrapers around People’s Park today, this old building remains distinctive with its unique terrazzo and red brick exterior, and its towering clock tower stands out prominently even when viewed from the surrounding high-rises.

A notable bronze plaque commemorates the members of the Republican-era Race Club who lost their lives during World War I.

The opening of the Shanghai History Museum resolved the long-standing issue of the original museum lacking a permanent address. It also filled a significant gap in Shanghai’s cultural landscape, as the city had been without a local chronicle-style museum for an extended period. As a renovated and reopened historic building, both its interior and exterior have been meticulously refurbished, enhancing its overall appeal. The newly renovated rooftop platform is now open to the public, offering panoramic views of People’s Park and the surrounding architecture, making it an excellent spot for sightseeing and photography.

The museum’s permanent exhibition is divided into four main sections: “Preface Hall,” “Ancient Shanghai,” “Modern Shanghai,” and “Epilogue Hall.” These are further divided into nine units, comprehensively reflecting Shanghai’s 6,000-year social development process and cultural-historical characteristics.

Visitors can access the exhibition halls on the second floor via elevator or stairs. The exhibition areas are spread across the second, third, and fourth floors. The first-floor exhibition space is reserved for temporary exhibitions.

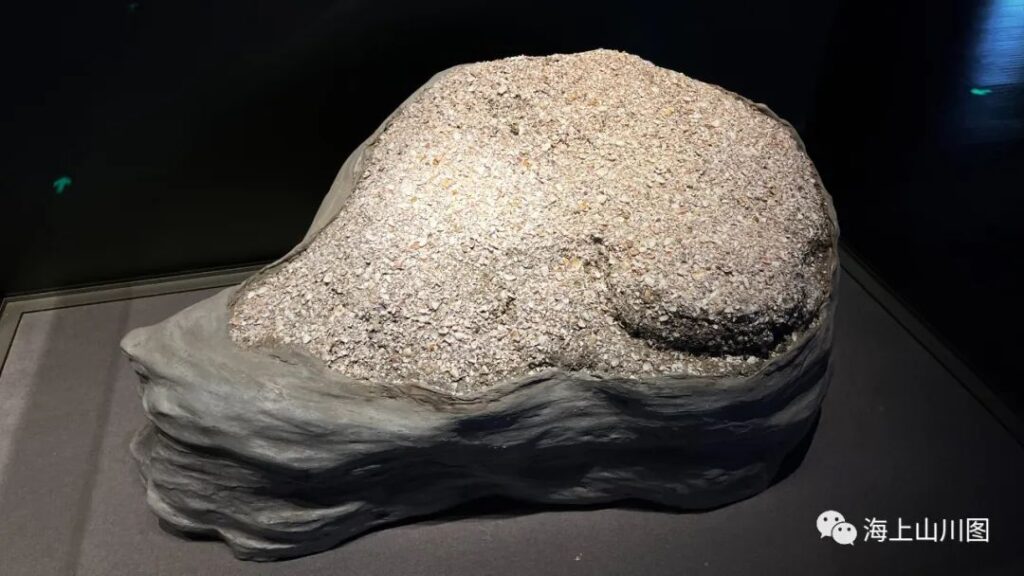

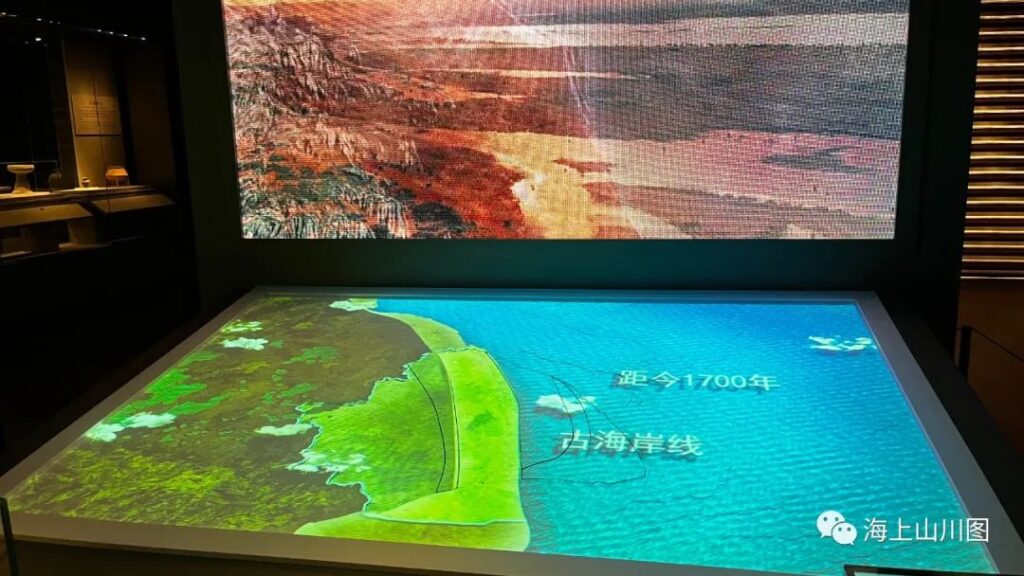

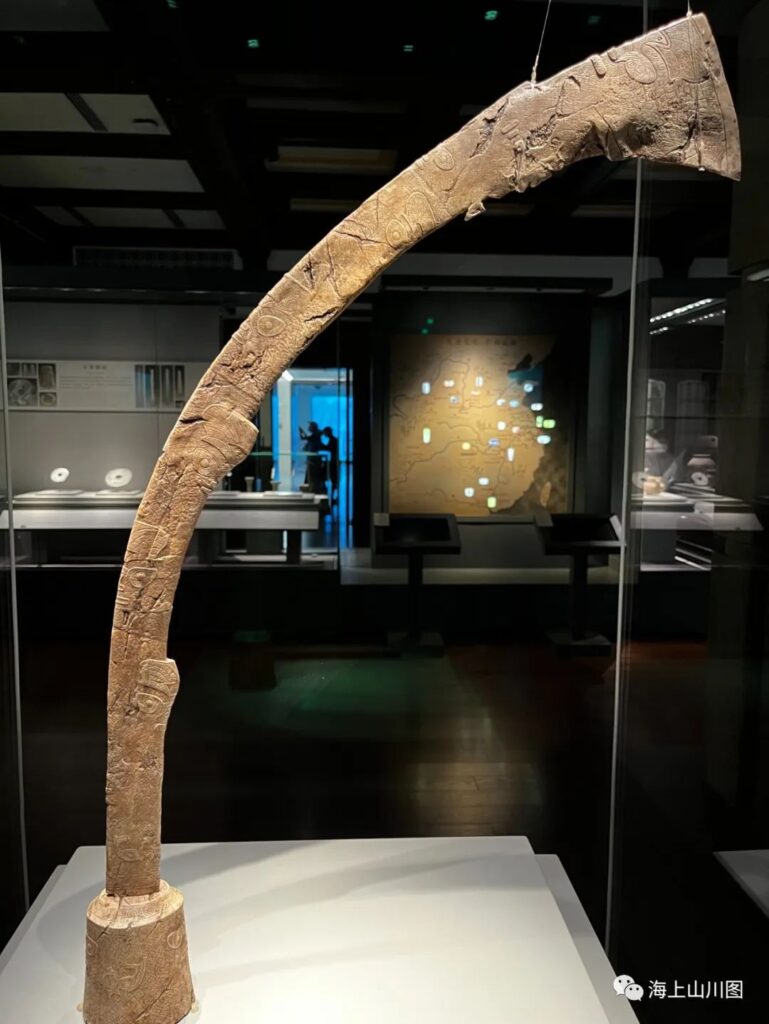

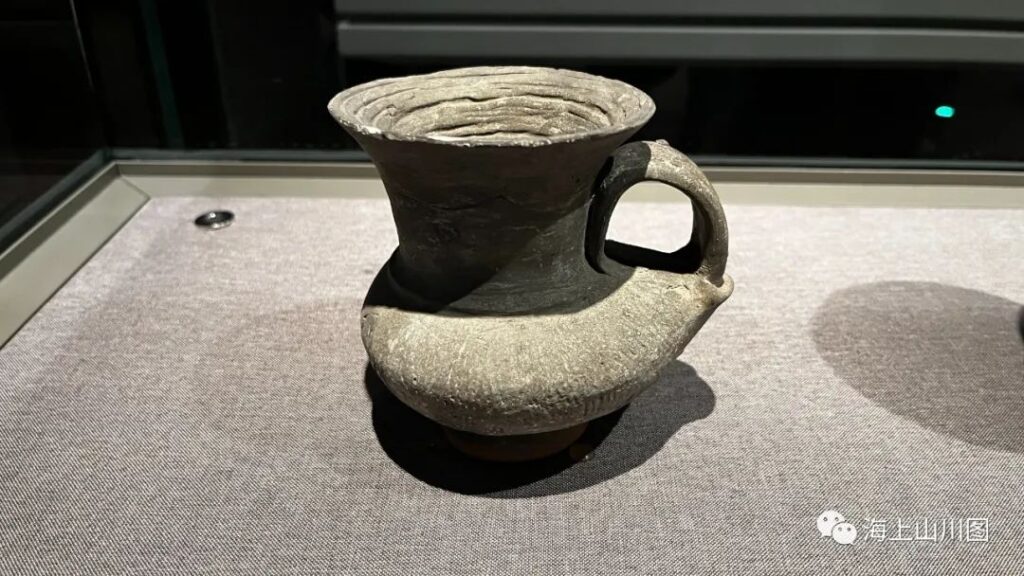

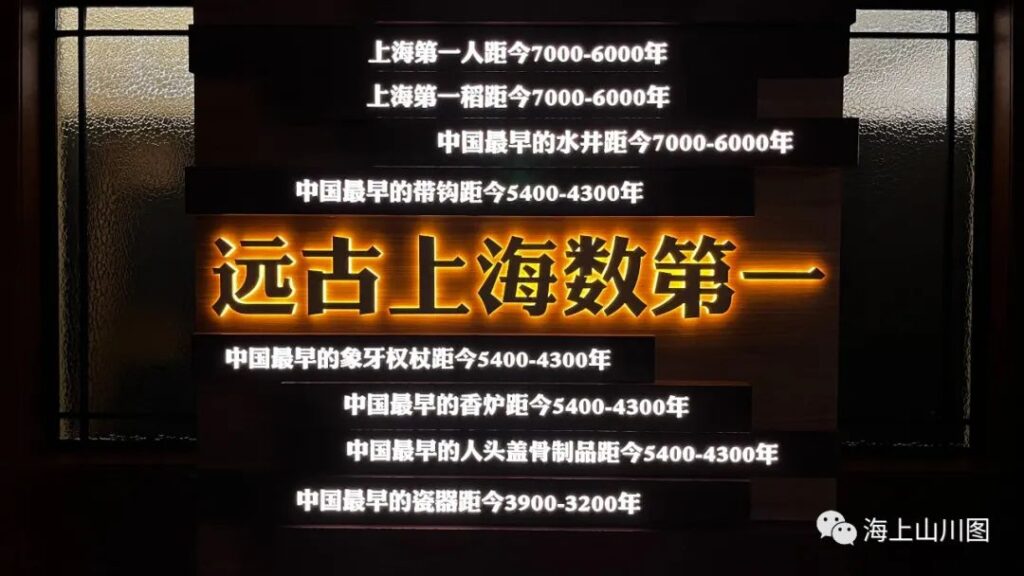

The “Preface Hall” opens with thought-provoking questions: “Where did Shanghai come from? Who were the earliest Shanghainese? Why did Shanghai become Shanghai?” It showcases the geographical evolution of Shanghai’s land formation and the development of prehistoric cultural lineages. Visitors can observe the changes in the ancient coastline and learn about various cultural types such as Songze, Liangzhu, Qianshanyang, Guangfulin, and Maqiao. The section concludes by highlighting several “firsts” in ancient Shanghai’s history.

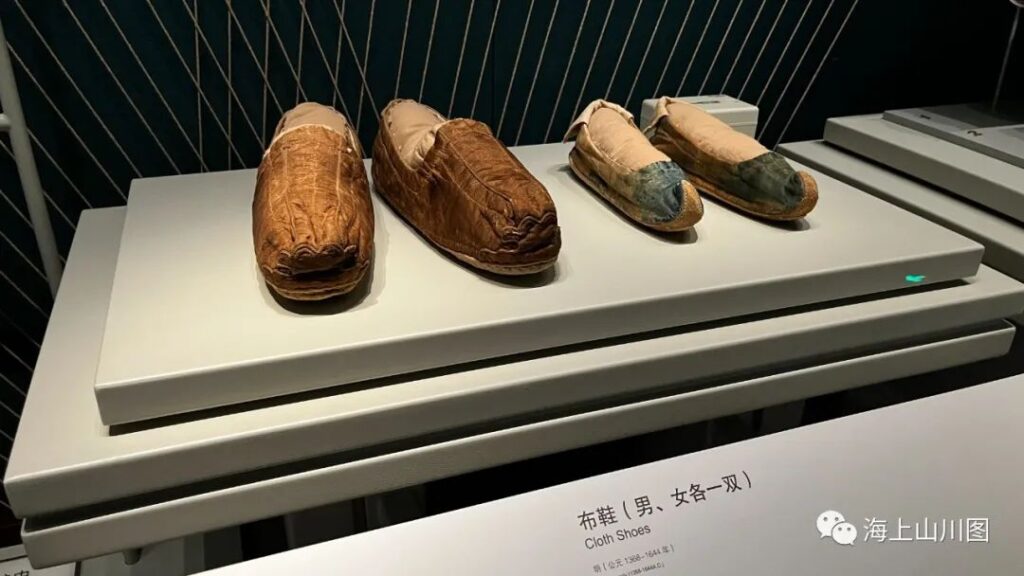

The “Ancient Shanghai” section introduces the social development of the Shanghai region from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods to the Qing Dynasty. It covers the administrative changes in ancient Shanghai, the development of culture and economy, and the rise of towns and commerce.

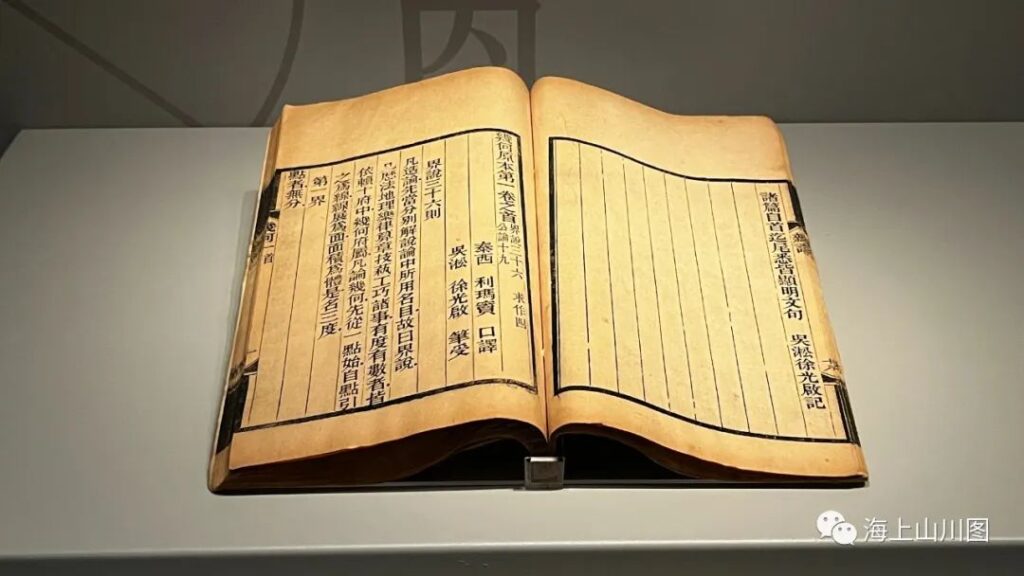

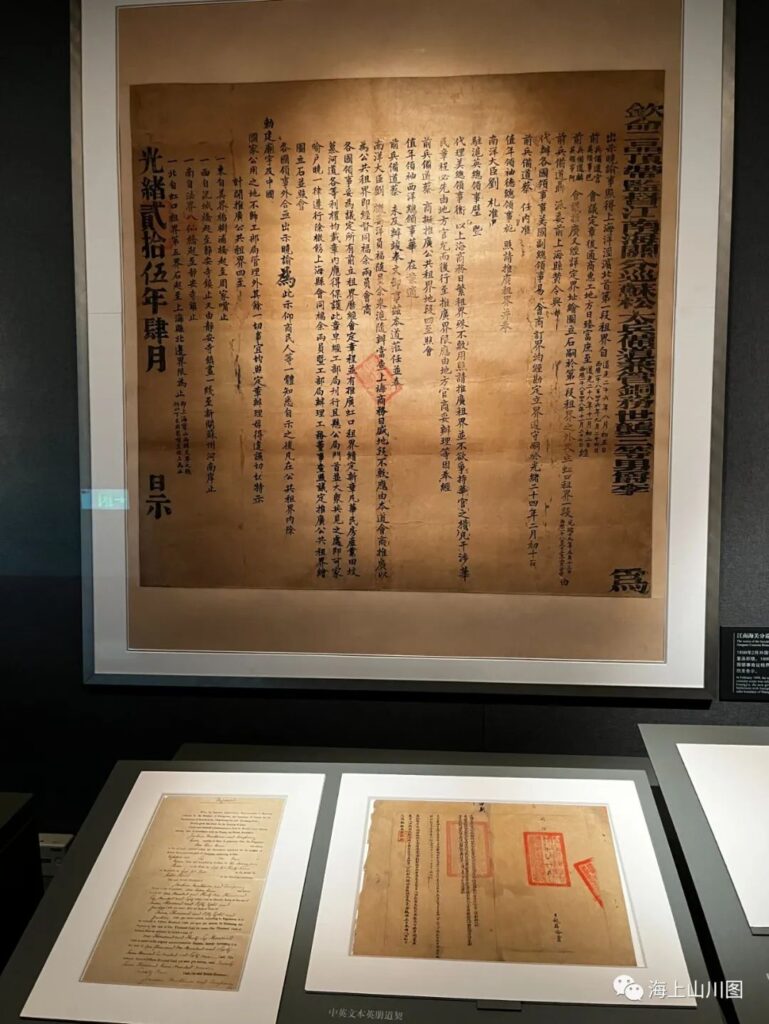

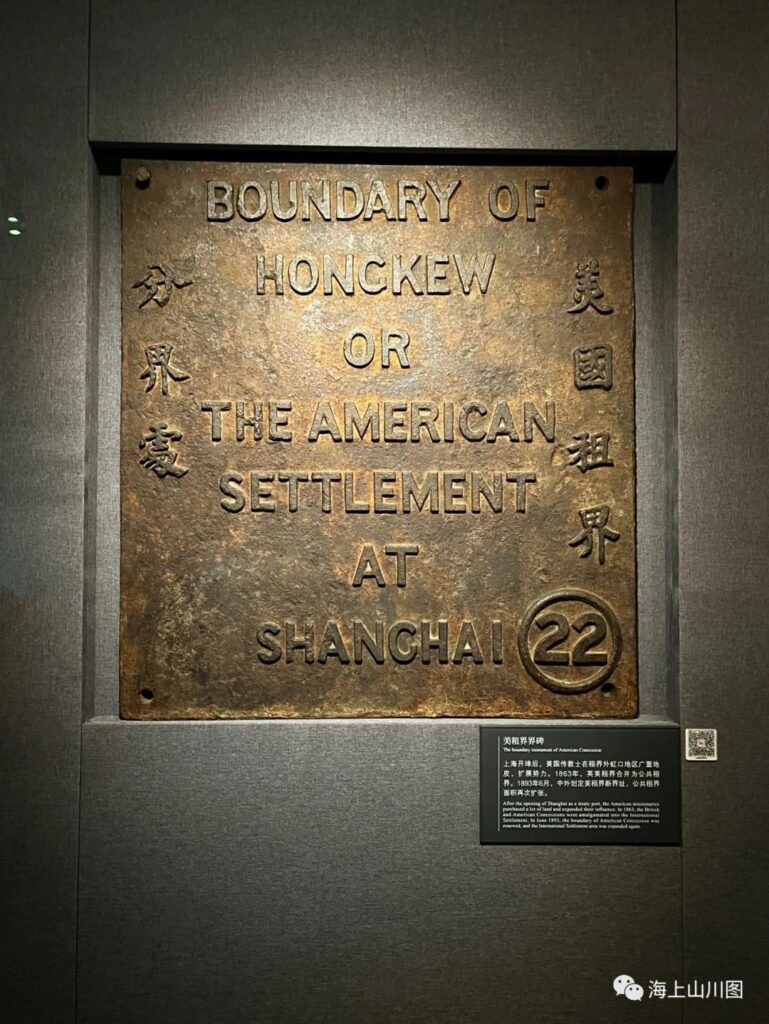

The “Modern Shanghai” section begins with the opening of Shanghai as a port city. It traces the city’s development from the outbreak of the Opium War and the establishment of foreign concessions. The exhibition showcases Shanghai’s evolution into the largest metropolis in the Far East during modern times, focusing on industrial and commercial development, as well as modern culture and education.

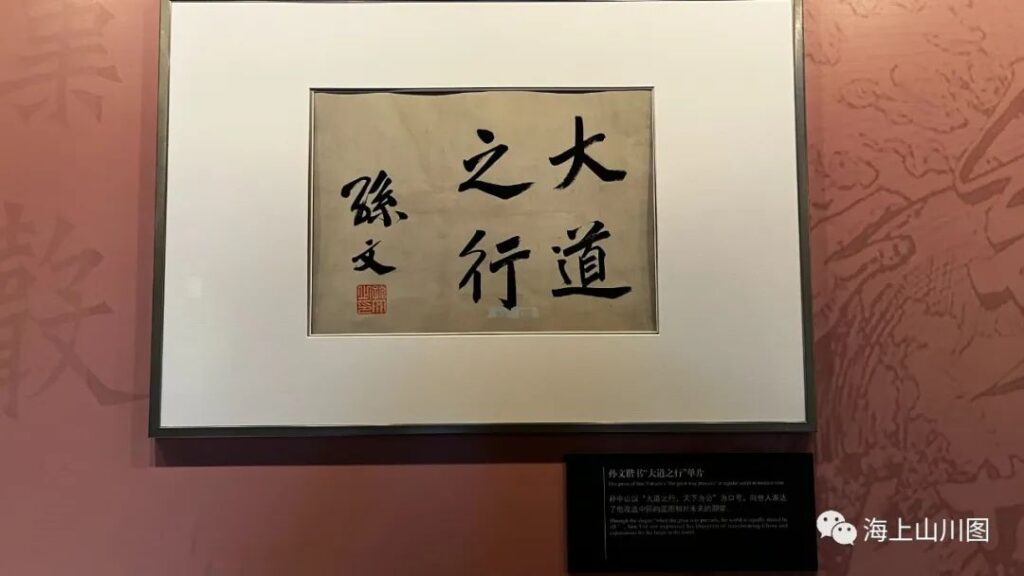

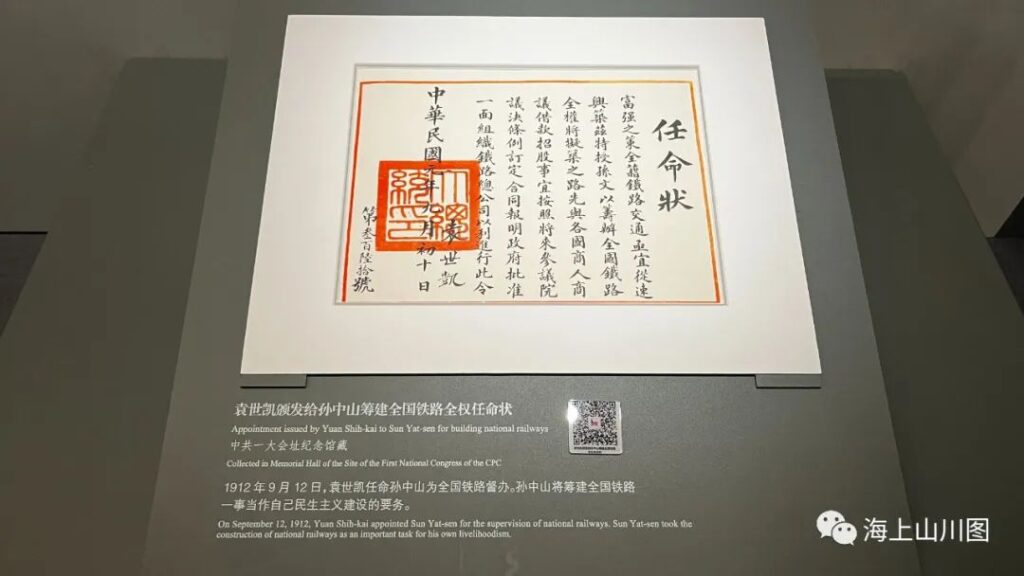

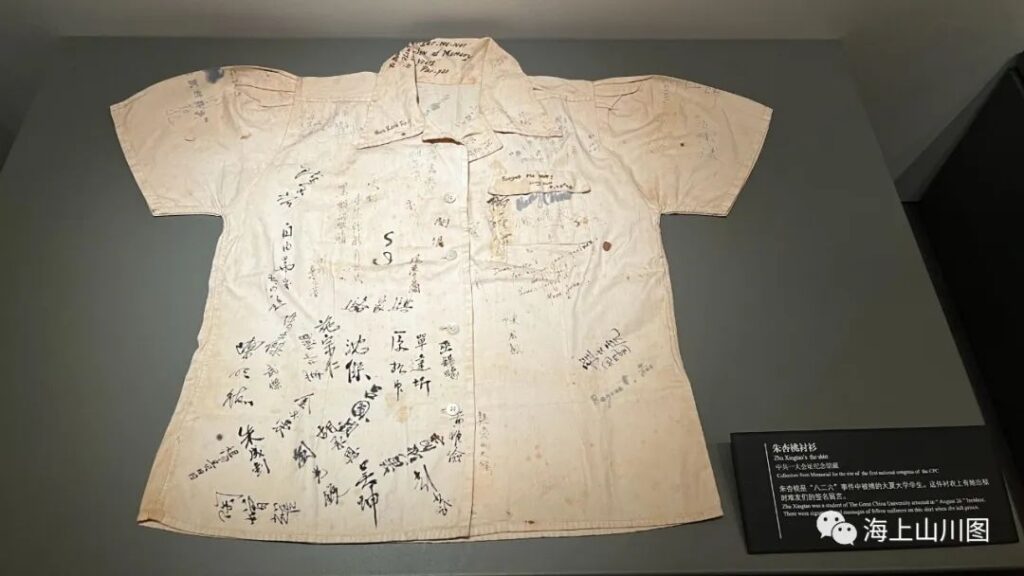

This section also highlights the impact of the Xinhai Revolution and the Nationalist Government’s “Greater Shanghai Plan” on the city’s development. Importantly, it emphasizes the birth of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai and its leadership in a series of revolutionary struggles, including resistance against Japanese invasion and the overthrow of the Nationalist Party’s rule, ultimately leading to national liberation.

The “Epilogue Hall” reflects on Shanghai’s achievements in various fields since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Throughout the museum, visitors can see many important cultural relics from the Shanghai History Museum’s collection, including:

- The aforementioned “General Zhenyuan” bronze cannon from 1841.

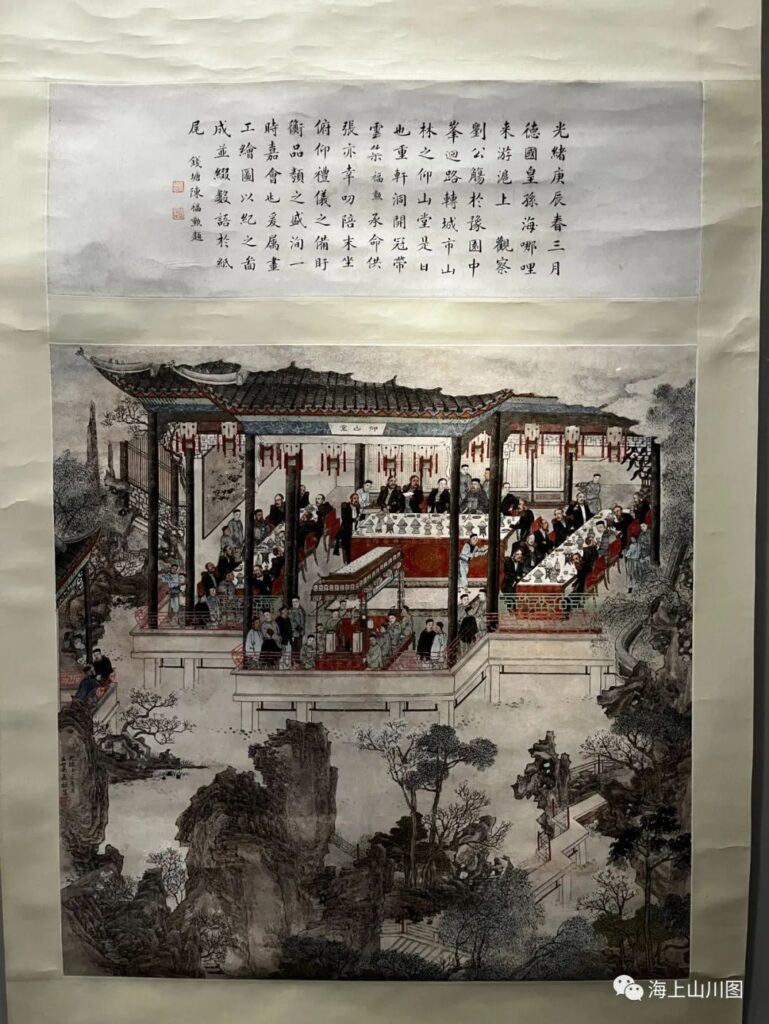

- The 1880 scroll painting of a banquet in Yu Garden by Wu You.

- A cotton ginning machine manufactured by the British Dabaisheng Company in 1895.

- Original manuscripts of the Dianshizhai Pictorial from the late Qing Dynasty.

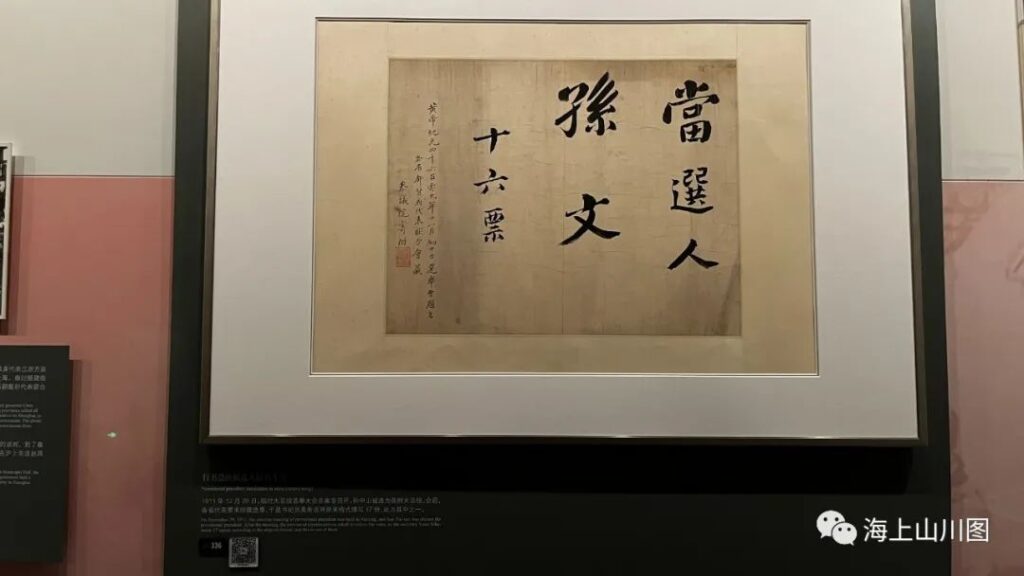

- Ballots from Sun Yat-sen’s election as Provisional President.

- A “Hundred-Character Sedan Chair.”

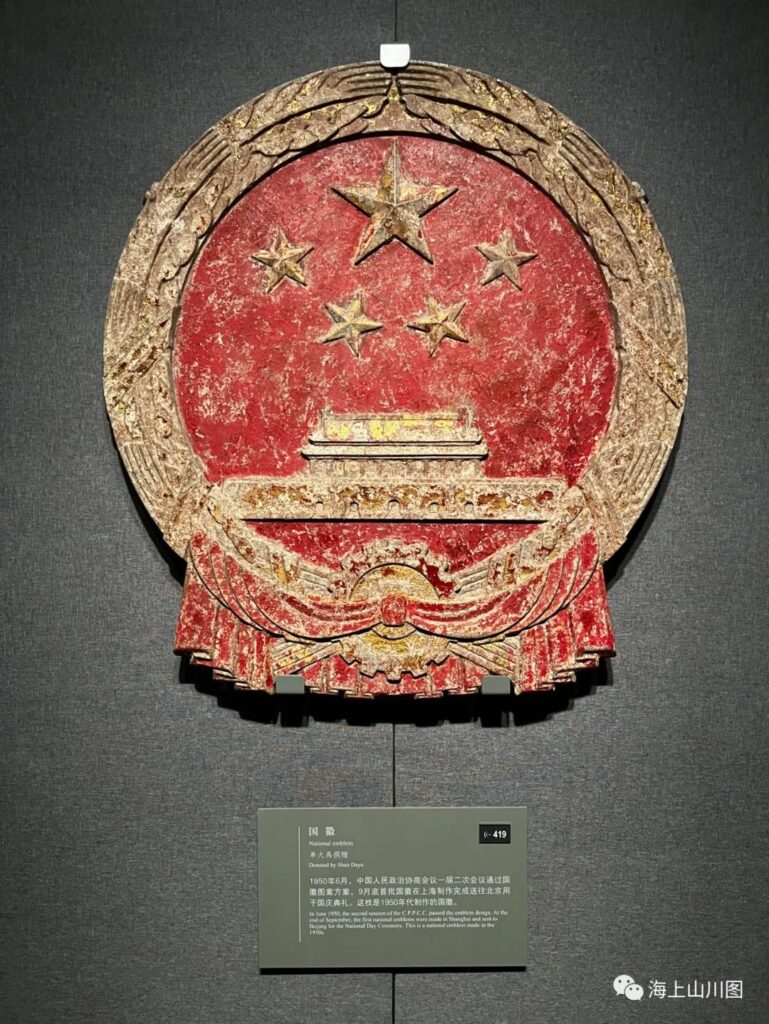

- The national emblem produced in the 1950s.

These exhibits provide a tangible connection to Shanghai’s rich history, from its early days as a growing port city to its development into a modern metropolis.