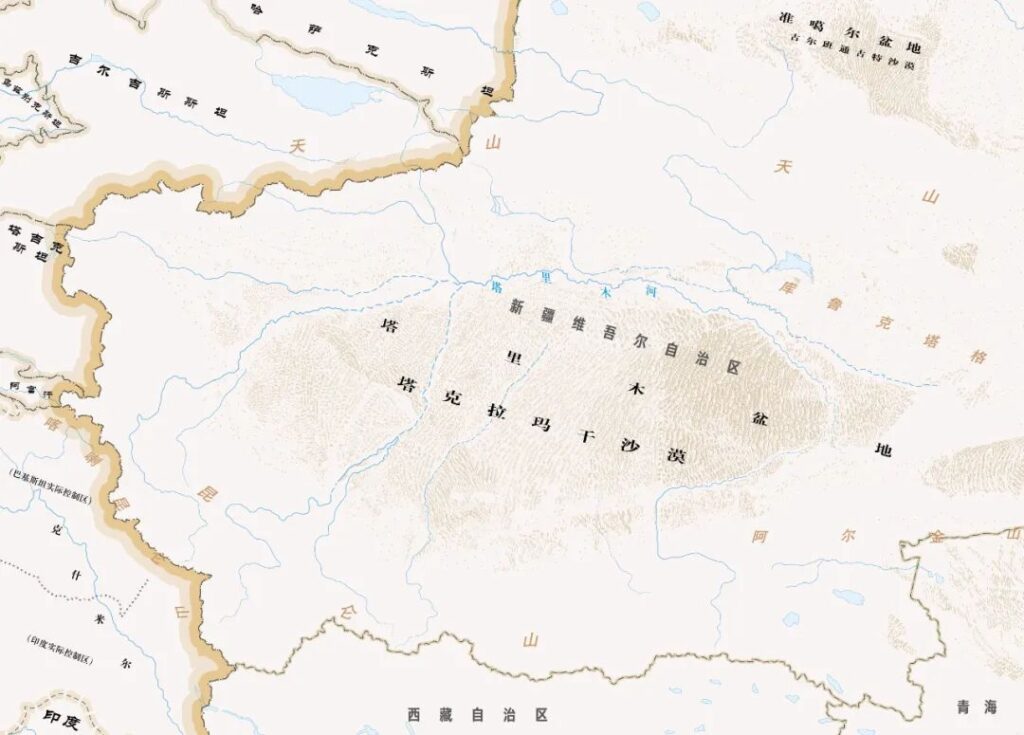

Deep in the Tarim Basin, in the heart of Central Asia, lies a region characterized by its arid climate and scarce rainfall. Due to its unique geographical and climatic conditions, this area has given rise to China’s largest desert – the Taklamakan. Those who venture into this sea of sand are invariably awestruck by its ever-changing, boundless expanse, reflecting on the brevity and insignificance of human life in comparison.

Deserts have long been symbols of desolation and harshness, places where life seems to be all but extinct. The Taklamakan, China’s largest desert, is no exception. It is extremely arid, often described as a “sea of death” or a “forbidden zone for life,” with an annual precipitation of only 10-38 millimeters.

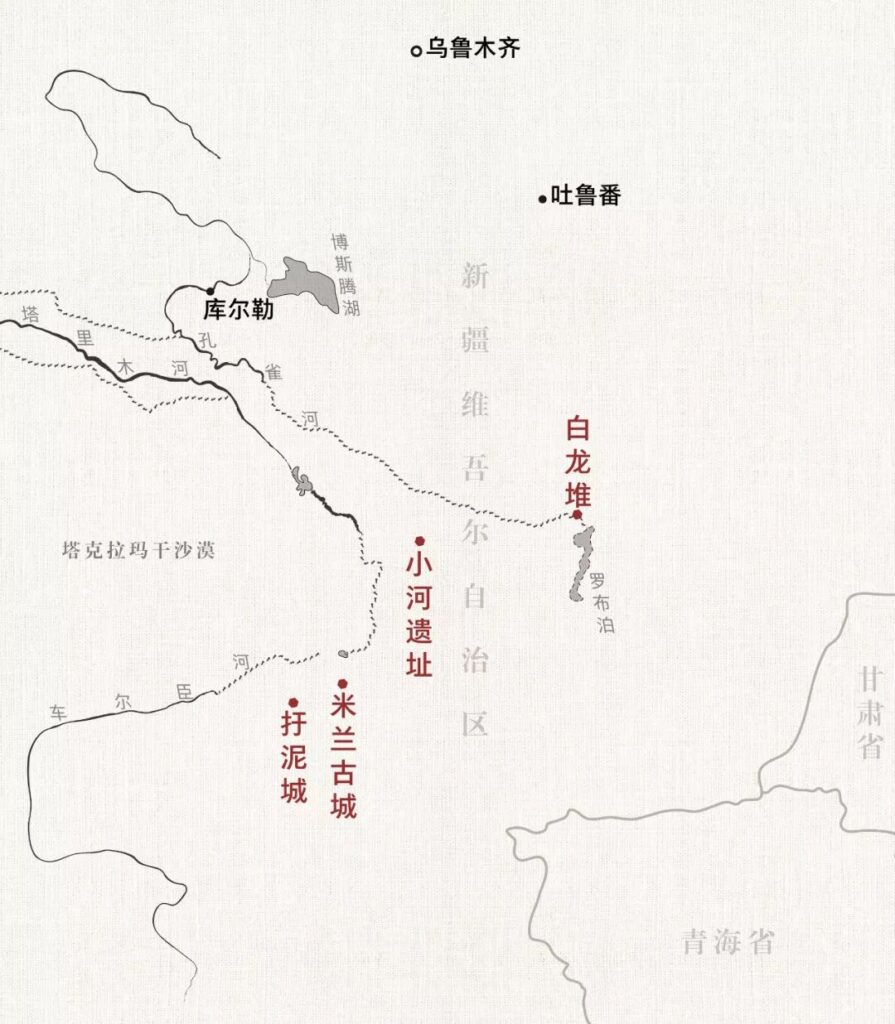

Throughout history, the Taklamakan has swallowed numerous civilizations, including Loulan, Xiaohe, and Jingjue. Even the ancient Silk Road had to skirt carefully along its edges.

The “Sea of Death”

Deserts are indeed inhospitable places for life.

Over a thousand years ago, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, on his journey to India, passed through the eastern part of the Taklamakan known as Moheyan Chi. He found himself stranded in the 800-li (about 400 km) stretch of desert for four to five days, plunging into despair. Suddenly, his experienced horse began to gallop wildly. He followed the horse for a long time until a clear spring appeared in sight, finally escaping the shadow of death.

Years later, recalling this desert, he still shuddered, saying, “For four nights and five days, not a drop touched my throat. My mouth and stomach were parched, and I was nearly finished.”

While the desert’s heat is certainly formidable, even more terrifying is its endless expanse. Tormented by thirst and scorching temperatures, many travelers and animals have perished, their remains reduced to bleached bones. When the wind blows, the eerie sounds resemble mournful wails, sending chills down one’s spine.

The Taklamakan is China’s largest desert. Of the country’s total desert area of about 800,000 square kilometers, the Taklamakan accounts for 365,000 square kilometers – nearly half of all desert land in China. It is also the world’s second-largest shifting sand desert, surpassed only by the Rub’ al Khali in the Sahara Desert region.

A “shifting desert” refers to a desert that tends to move in the direction of prevailing winds, continuously migrating. The Taklamakan is primarily influenced by northwesterly winds. Over the past millennium, the entire desert has extended about 100 kilometers towards the southeast or slightly east.

The Taklamakan Desert experiences extreme temperature variations between day and night, with differences reaching over 40°C. During scorching summers, temperatures can soar to 67.2°C, with sand surface temperatures sometimes exceeding 70°C. Without proper protection, human skin can easily suffer burns.

However, millions of years ago, the Taklamakan Desert bore a vastly different appearance.

This area was once a vast ocean. As tectonic plates shifted, the sea receded, and land emerged. The rise of the Tibetan Plateau blocked moisture, leaving the already inland Tarim Basin with little rainfall.

Combined with years of wind erosion, exposed soil and rocks were gradually stripped into fine sand. Meltwater from surrounding plateaus and mountains formed rivers, depositing thick layers of loose sand. In the arid environment, these sand layers were lifted by the wind, accumulating over time to form the vast desert.

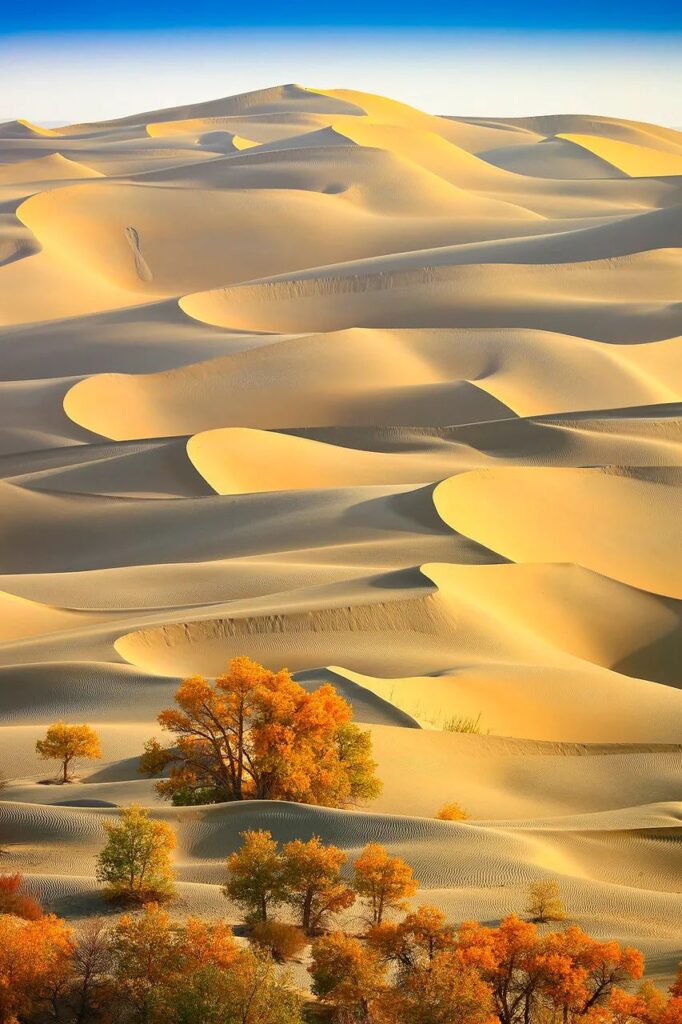

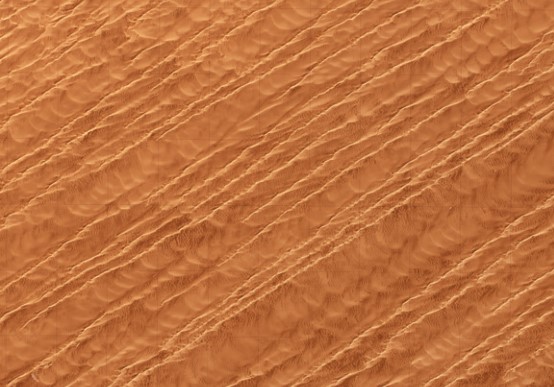

This desert is the largest in China and boasts the most diverse types of sand dunes. Desert expert Zhu Zhenda states, “The Taklamakan is a museum of wind-sand landforms.”

In the Taklamakan Desert, shifting sand dunes cover 82% of the area, while fixed and semi-fixed dunes account for only 18%. The landscape is dominated by exposed giant sand dunes, with 80% of the shifting dunes reaching heights of over 50 meters. The tallest dunes can reach up to 300 meters, exhibiting various shapes.

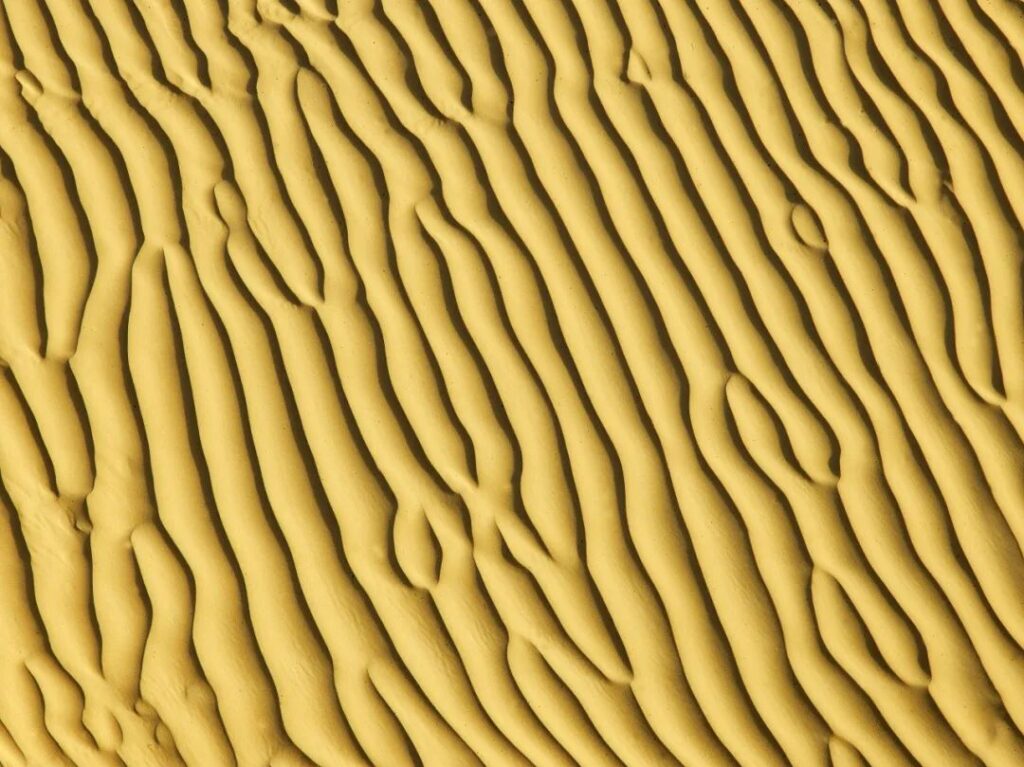

Regardless of their shape, all dunes are directly related to wind patterns. Wind sculpts the dunes’ forms and determines their direction.

Transverse dunes are formed under the influence of unidirectional winds, winds from two opposite directions, or winds from two nearly perpendicular directions. Among these, shifting dunes include crescent-shaped dunes and dune chains, compound crescent-shaped dunes and compound dune chains, compound sand mountains, and reticulate dunes. Fixed and semi-fixed dunes include ridge-and-hollow dunes and rake-like dunes.

Longitudinal dunes are formed under the influence of winds from two acute-angled directions or unidirectional winds. Shifting dunes include crescent-shaped sand ridges, sand ridges, and compound sand ridges. Fixed and semi-fixed dunes include dendritic sand ridges.

Multi-directional wind dunes are formed under the influence of multi-directional winds with one or several dominant directions, or multi-directional winds of relatively uniform strength. Shifting dunes include pyramid dunes (star dunes), linear compound pyramid dunes (linear star dunes), dome-shaped dunes (circular dunes), and honeycomb dunes.

Some scholars refer to deserts larger than 30,000 square kilometers as “sand seas.” Standing atop a dune in the Taklamakan and gazing into the distance, one sees undulating dunes resembling ocean waves stretching endlessly. When a sandstorm strikes, it’s like a towering tsunami, obscuring the sky and threatening to engulf everything in its path.

Desert and Oasis

Our perception of deserts might be that of desolate, lifeless places, but deserts are not seas of death.

The Taklamakan Desert, located in the Tarim Basin, is far from the ocean and surrounded by plateaus and mountains, making it extremely arid. However, while these highlands block moisture, they also provide precious meltwater from snow and ice.

Meltwater from ice and snow gathers into babbling streams that meander through the desert. Rivers of various sizes often flow independently, not connecting to external water systems. They either empty into lakes or simply disappear into the desert.

Among these, the Tarim River is China’s longest inland river, stretching about 2,200 kilometers. Some sections lack a fixed riverbed, with water flowing freely and unpredictably, earning it the nickname “the untamed horse.”

The final destination of the Tarim River and many other inland rivers is the lowest point of the Tarim Basin – Lop Nur. This area was once lush with water and grass, and was China’s second-largest lake after Qinghai Lake.

Water brings oases. The Taklamakan is known as the “home of the Populus euphratica,” with reportedly 90% of China’s Populus euphratica trees found here. Some plants have developed extensive root systems to cope with water scarcity, with roots extending tens or even hundreds of times longer than their above-ground parts to absorb underground moisture. Animals have adapted to extreme heat and food shortages by developing summer dormancy.

Oases nurture various life forms and catalyze civilizations. The snow-capped mountains melt in spring, with water cascading down like the flowing hair of goddesses. The oasis cities that emerge are like green jewels adorning this landscape.

From the late Paleolithic period about 10,000 years ago, groups belonging to Mongoloid or Europoid races began living in these oases. The famous “Loulan Beauty” from Tiemenguan is believed to be from a Europoid branch – the Tocharians. These people hunted, fished, farmed, and wove, multiplying and forming settlements and even cities.

The oldest known city ruins in Xinjiang are located near the Yarkand River in Yarkant County. This ancient city, known as the Langan site, was established between the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

Loulan is the most famous of these desert civilizations. Nourished by Lop Nur, it was recorded in the “Records of the Grand Historian”: “Loulan, an ancient walled city by the salt marsh.” The salt marsh refers to the ancient name of Lop Nur. This legendary kingdom of the Western Regions was originally located at a crucial point on the Silk Road, where goods from various places gathered, making it prosperous and peaceful.

However, due to climate change and human activities, the once vast lake has been reduced to large expanses of salt crust, with the surrounding ecosystem deteriorating as a result. Loulan has silently disappeared, its presence now only preserved in ancient poetry: “I wish to use the sword at my waist to conquer Loulan,” and “I shall not return until Loulan is defeated.”

If human civilizations are compared to stars, desert civilizations are like meteors. Arid regions receive little precipitation, and civilizations established here rely heavily on meltwater from ice and snow.

In such a unique environment, any change in river courses or drying up of lakes can have a devastating impact on water-dependent residents, leading to the abandonment of city-states. The civilization brought about by the environment is also dissolved by environmental changes.

The ecosystem in arid regions is particularly fragile, unlike the more resilient eastern monsoon regions. The regional environment is highly sensitive to human activities, with soil prone to salinization and alkalization, becoming infertile after years of cultivation. One theory suggests that Loulan’s downfall was due to environmental degradation caused by excessive farming.

In the desert, many civilizations appeared fleetingly and vanished quickly. It is precisely because of this that civilizations continuously replaced and merged with one another, buried by wind and sand until rediscovered by people.

Museum of Civilizations

The Taklamakan is not just a museum of landforms; it is also the world’s largest underground treasure trove of civilizations.

While the desert has swallowed countless lives, it has preserved the city-states and artifacts created by humans. Due to the dry conditions, murals and sculptures are less susceptible to water and biological erosion, allowing these relics to be well-preserved, forming a natural museum.

After 15 centuries, Loulan resurfaced, allowing us a glimpse of its former glory. Various artifacts such as pottery, lacquerware, woodware, bronze ware, and glassware showcase the city’s past prosperity and diverse goods. Most striking are the colorful Han Dynasty silk brocades.

The ruins of Milan ancient city contain Buddhist stupas, temples from the Wei and Jin periods, and Tibetan fortresses. The discovery of “winged angels” in the temple murals attracted significant attention worldwide.

The Niya site has yielded wooden slips written in Kharoshthi script, originating from the western Gandhara region, as well as brocades bearing the inscription “Five stars rise in the east, benefiting China.”

The artifacts unearthed from beneath the Taklamakan Desert are astonishingly diverse. Besides murals and brocades, Roman columns and Indian Buddha statues have been discovered, confirming that this central section of the Silk Road was the world’s only convergence point of four major civilizations.

While the ancient desert has consumed many lives, some forms of life have adapted to the environment and flourish here.

Human activity has always been present in the Taklamakan. In the heart of the desert lies a mysterious oasis known as the “navel of the Taklamakan Desert.” Its mystique stems from its isolated survival in the center of the world’s second-largest desert, undocumented for centuries and completely cut off from the outside world. Moreover, the history of this place and its inhabitants remains unclear.

Locals call this place “Daryabuy,” meaning “along the great river” in Chinese. In 1982, oil-seeking desert vehicles entered Daryabuy from the north. The sudden roar and rolling of these “behemoths” stunned the herding men, while the exploration team members were equally shocked to discover “long-tailed wild men” deep in the desert.

In reality, this has always been a village under the jurisdiction of Yutian County. The locals speak Uyghur, practice Islam, and call themselves Keriya people. With over 260 households and nearly 1,300 people, they lead a simple life of “a flock of sheep, a well, and a few rooms.”

The so-called “tails of the wild men” were actually long axe handles tucked behind the waists of the Keriya people. The local livestock, mainly sheep, feed on poplar leaves and reeds. Keriya herders don’t need whips for herding; instead, they use axes to cut poplar branches for the sheep to eat and to chop dead poplars for firewood used in cooking and heating. It can be said that axes are indispensable in the lives of the Keriya people.

Today, it’s still difficult to find Daryabuy on most Chinese maps. However, its international renown, especially in geography, history, and archaeology circles, is comparable to that of the Loulan ruins.

Geography has constrained the development of civilizations, while civilizations, in turn, have influenced the changes in landscapes. Lop Nur once nurtured a brilliant civilization but gradually dried up due to climate change and human activities. During the 1958-1959 expedition, scientists lamented that it might be the last time humans could sail on Lop Nur.

In 1961, Lop Nur completely dried up, resembling a giant ear listening to Earth’s past events. It was here that New China’s first atomic bomb was detonated, and it swallowed explorers like Peng Jiamu and Yu Chunshun, becoming a symbol of barren land.

Today, Lop Nur once again has boundless blue waters. People discovered rich potassium salt deposits here and pumped underground brine to the surface, reforming lakes. The square salt lakes look like turquoise inlays on this giant ear.

Water bodies have a significant regulatory effect on climate. According to potash company employees, the entire region has become cooler and rainier in recent years. If you visit Lop Nur now, you might even encounter moderate rain.

The “revival” of Lop Nur represents another human civilization’s choice for arid regions. It’s reported that the potassium salt here can be mined for 30 years. What will happen to Lop Nur after 30 years? It’s hard to imagine now. Its fate is once again in human hands.

Today, we can build long roads through shifting deserts. The Tarim Desert Highway is the world’s longest road built through shifting sand, stretching 522 kilometers. Like an artery, it runs through the entire desert, serving as a bridge across the sea of sand. As human actions increasingly impact the environment, we should be more cautious in ecologically fragile areas.

The Taklamakan Desert embraces and breathes in everything from ancient times to the present with its broad bosom. The sighs in the wind and sand have faded away, but we can still hear the crisp sound of camel bells. The majestic desert is not a sea of death; it has always contained infinite vitality.