Tianxin Park, situated in the heart of Changsha city, is a classical garden-style park featuring ancient city walls and pavilions as its main attractions. Despite its modest size, the park boasts exquisite and elegant pavilions, landscape designs seamlessly integrated with the surrounding ponds and vegetation, and winding paths that meander through the lush bamboo groves and famous trees. The limited space within the park encapsulates an infinite sense of poetic charm.

Upon entering the park through the northeast gate, visitors are greeted by an array of inscribed tablets, pavilions, galleries, artificial hills, and winding ponds. The vibrant flowers and lush greenery create a picturesque scene that changes with every step. The park also offers teahouses and study rooms, providing ideal spots for leisure, entertainment, and socializing. Tianxin Park is a beloved destination for Changsha residents to relax and unwind, where they engage in activities such as chatting, singing, dancing, exercising, playing chess, and playing musical instruments, all in a tranquil and carefree atmosphere.

Tianxin Park is a park that encapsulates the struggles of the Hunan people throughout history, bearing witness to Changsha’s journey from the depths of time. The “Xunfeng Pavilion” is a granite pavilion, its name derived from the ancient folk song “Nanfeng Ge,” which includes the lyrics “The southern wind’s fragrance can soothe our people’s resentment.” The original Xunfeng Pavilion was a wooden structure that was destroyed during the “Wenxi Fire” in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The current stone pavilion was rebuilt in 1987.

The Historical Figures Stone Carving Gallery features engravings of 33 historical figures who had a significant impact on Hunan. Among these notable individuals are: the legendary Emperor Yan, also known as Shennong, from mythological tales; Jia Yi, a thinker from the Western Han dynasty; Zhu Xi and Zhang Shi, Neo-Confucian philosophers from the Northern Song dynasty; Li Fei, a loyal and heroic figure who resisted the Mongol invasion during the Southern Song dynasty; Zeng Guofan, a leader of the Self-Strengthening Movement in the Qing dynasty; Wei Yuan, a pioneer who opened his eyes to the world; and Guo Songtao, a diplomat from the late Qing period.

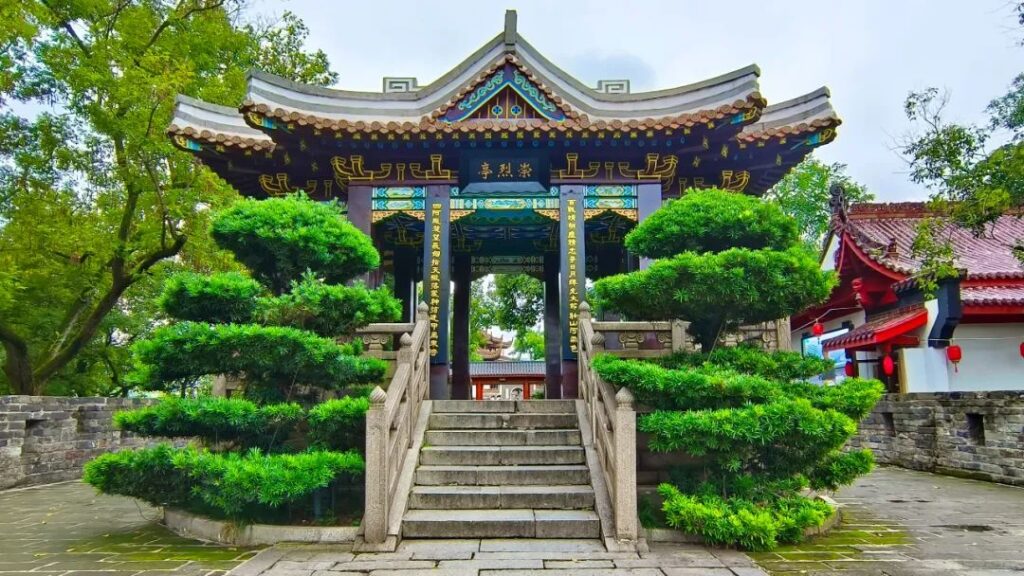

Following the main path of the park, visitors come across a set of granite structures, namely the Chonglie Pagoda, Chonglie Gate, and Chonglie Pavilion. From September 1939 to February 1942, the Chinese army engaged in three large-scale offensive and defensive battles against the invading Japanese forces in Changsha, also known as the “Changsha Battles.” Statistics show that during these three battles, the Chinese army suffered 93,944 casualties, including those killed in action, wounded, and missing, while eliminating over 110,000 Japanese soldiers in total.

In 1946, to commemorate the soldiers who sacrificed their lives in the Changsha Battles, this group of memorial buildings was constructed at the northern end of the Tianxin Pavilion city wall. The Chonglie Pagoda has a hexagonal base, with a circular disc and cylinder forming the pagoda’s body. A globe sits atop the cylinder, with a map of China engraved on its surface. A stone lion stands proudly above the globe, symbolizing the inviolable national spirit of Chinese territory.

The “Chonglie Gate” is a four-pillar, three-door archway-style structure. The central couplet on the gate pillars reads, “Courage to devour the invaders, bravely defending the mountains and rivers.” The couplets on the side pillars, written in seal script, state, “Facing difficulties and forgetting one’s own death, desiring something greater than life itself.” These two sets of couplets highly praise the spirit of the soldiers who fought bravely and selflessly during the war.

The predecessor of the Chonglie Pavilion was the Noon Gun Pavilion. During the late Qing dynasty and early Republic of China, a brass cannon was placed in the pavilion to unify the time throughout the city. The cannon was fired three times every day at noon to signal the time. In 1929, to commemorate the compatriots who perished in the “May 30th Tragedy” in Jinan, the noon gun was removed, and the pavilion was rebuilt as the National Humiliation Pavilion, which was later destroyed in the “Wenxi Fire.” In 1946, the Chonglie Pavilion was constructed on the original site of the National Humiliation Pavilion to honor the soldiers who died in the Changsha Battles. The pavilion features sixteen pillars, interlocking wooden brackets, and an octagonal Xieshan-style roof.

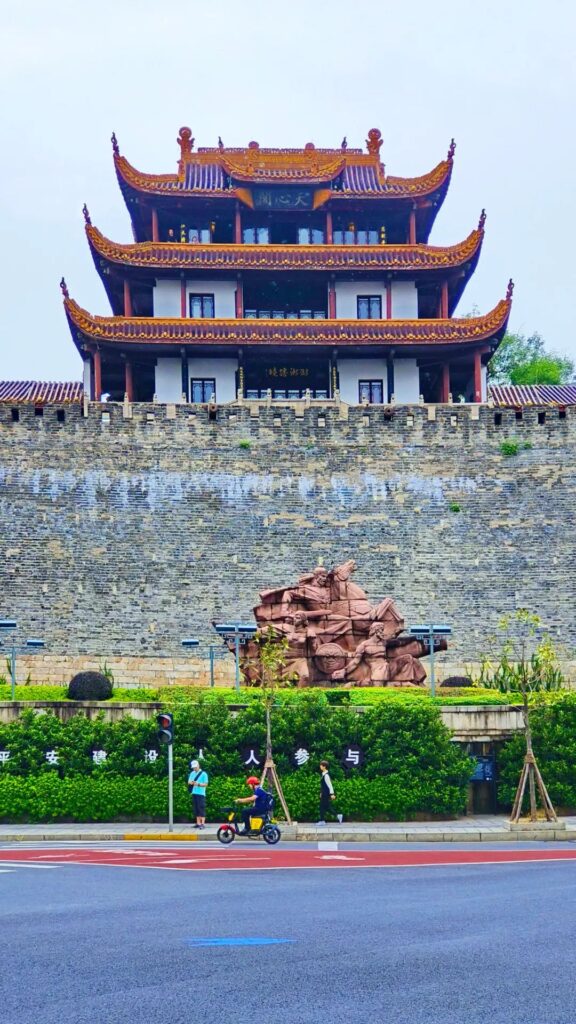

Beyond the Chonglie Pavilion stands the wide ancient city wall of Changsha. According to the “Commentary on the Water Classic” by Li Daoyuan of the Northern Wei dynasty, in 202 BC, Wu Rui was granted the title of King of Changsha by Liu Bang for his contributions to the overthrow of the Qin dynasty, and Changsha began constructing earthen city walls. During the Hongwu era of the Ming dynasty, the Changsha Defense Commander significantly renovated and reinforced the city walls, replacing the earthen walls with stone foundations and brick construction. At the end of the Ming dynasty, Zhang Xianzhong captured Changsha, and the city walls suffered damage.

In the early Qing dynasty, Hong Chengchou governed Changsha and repaired the city walls using bricks and stones from the former Ming prince’s mansion. During the Kangxi era, Huguang Province was divided into Hubei and Hunan, with Changsha becoming the capital of Hunan Province. The city walls underwent further repairs, resulting in a semi-circular, double-walled layout. During the Republic of China period, the Changsha government at the time demolished most of the city walls to construct a ring road around the city, preserving only the section of the wall at Tianxin Pavilion as a testament to Changsha’s historical development.

Upon the ancient city wall, the massive battlements silently extend upward. A curved wall resembling a cat’s arched back appears before you, with the characters “Xiong Zhen” (Heroic Garrison) inscribed above the gate and “Xiaoqiao Gu Ge, Qin Han Ming Cheng” (Ancient Pavilion of Xiaoxiang, Famous City of Qin and Han) on either side. Entering through the gate, you find yourself in an area with a profound historical atmosphere, where the renowned Tianxin Pavilion of Changsha is located. The site of Tianxin Pavilion, known as Longfu Mountain in ancient times, is the highest point in the center of Changsha.

Legend has it that a Xun Dragon lies beneath Longfu Mountain, a propitious sign of flourishing literary fortune. Therefore, the ancients constructed two pavilions, “Tianxin” and “Wenchang,” on the city wall. Both pavilions were later destroyed, leaving only a plaque bearing the name “Tianxin.” A new pavilion was then built next to the ruins of Wenchang Pavilion and named Tianxin Pavilion. The exact year of construction for Tianxin Pavilion, a symbol of Changsha, is unknown, with the earliest records dating back to the Wanli era of the Ming Dynasty, more than 400 years ago.

During the Ming Dynasty, Tianxin Pavilion was a single-story building. It was renovated into a two-story structure during the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty and further expanded to three stories during the Jiaqing era. In 1924, the renowned designer Liu Dunzhen from Hunan University redesigned and reconstructed Tianxin Pavilion. Unfortunately, the rebuilt pavilion only stood for ten years before being destroyed in the “Wenxi Fire” during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. In 1983, the Changsha municipal government rebuilt Tianxin Pavilion according to the 1924 blueprint.

In the pavilion area, I saw three buildings with green-tiled flying eaves and vermilion beams adorned with painted brackets. The central three-story building standing on a granite base is the main hall of Tianxin Pavilion, with a plaque reading “Chu Tian Yi Lan” (A Glance at the Chu Sky) hanging under the eaves. The two-story buildings on either side of the main hall are the auxiliary buildings. The northern auxiliary building is named “Bei Gong” (North Arch), while the southern one is called “Nan Ping” (South Screen). The three buildings are connected by walkways.

Due to its high elevation, Tianxin Pavilion was a strategically important location for both offense and defense, naturally becoming a must-seize spot for military forces. To enhance the city’s defensive capabilities, Tianxin Pavilion was fortified with inner and outer walls, with the outer wall further divided into southern and northern crescent-shaped sections. The city wall also featured eight gun ports, and the crescent-shaped enclosures could accommodate hundreds of soldiers. However, there was no city gate at the foot of Tianxin Pavilion, which could be confusing for enemies unfamiliar with the situation, as if they had stumbled into a maze.

In 1852, Xiao Chaogui, the West King of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, led his army to attack Changsha. Seeing the towering Tianxin Pavilion from afar, he mistook it for the main gate of Changsha. The Taiping Army then launched fierce attacks on the city wall of Tianxin Pavilion, but each assault ended in failure. West King Xiao Chaogui was hit by cannon fire from the city wall during the intense battle and succumbed to his injuries. The Taiping Army had no choice but to turn towards Hubei to continue their campaign.

Changsha became the only city along the Taiping Army’s advance that remained unbreached. Even today, one can still see the shell marks left on the city wall from that year. At the foot of the Tianxin Pavilion’s city wall, the sculptural group “Taiping Army Spirits” recreates the scene of West King Xiao Chaogui leading the Taiping Army in their attack on Changsha. This is one of the few sculptural groups in Changsha, and the entire sculpture is made of Sichuan Jiangjun granite.

Tianxin Pavilion is a building that has witnessed the vicissitudes of history. In 1905, Chen Jiading, a member of the Tongmenghui (Chinese United League), was entrusted by Huang Xing to return to Hunan and establish the Hunan branch of the Tongmenghui, setting up a secret headquarters on the third floor of Tianxin Pavilion. In 1911, Changsha revolutionaries held a meeting in the pavilion, secretly planning to support Huang Xing’s Guangzhou Uprising and organizing the Changsha Uprising. In 1930, Peng Dehuai led the Red Army to occupy Changsha and set up a temporary command post in Tianxin Pavilion.

Ascending the steps and entering the main hall on the first floor of Tianxin Pavilion, you can see a statue of the “Wenchang Emperor” beneath a plaque that reads “Flourishing Literary Fortune.” The Wenchang Emperor, also known as the Wenchang Star, is a deity revered in folk religion and Taoism, believed to govern the success and official ranks of scholars. In the past, many people came here to worship the Wenchang Emperor, praying for Changsha’s literary prosperity and blessings for their descendants to pass the imperial examinations.

Like all famous landmarks, Tianxin Pavilion has attracted numerous literary figures throughout history, becoming a gathering place for poets and scholars to compose and recite their works. Li Dongyang, the prime minister of the Ming Dynasty, wrote a couplet here: “The islets on the water are tied to boats; the boats move, but the islets do not. The Tianxin Pavilion is perched with pigeons; the pigeons fly, but the pavilion does not.” The Qing Dynasty poet Li Shaojun’s poem “Ascending Tianxin Pavilion on an Autumn Day and Gazing Afar” vividly describes the beauty of Tianxin Pavilion.

The great leader Mao Zedong had a special fondness for Tianxin Pavilion. When he was studying at the First Normal School of Hunan, he often climbed to the top of Tianxin Pavilion to enjoy the panoramic view and sit on the city wall to read. In 1960, during his inspection tour of Changsha, Mao Zedong once again ascended this ancient city wall. Looking at the former site of Tianxin Pavilion, he reminisced about the once-towering pavilion and remarked with emotion, “The pavilion has weathered storms, and the old memories are hard to forget!”

Ascending to the third floor of Tianxin Pavilion, the view suddenly becomes vast and open, truly giving the feeling of “gazing a thousand miles and overlooking ten thousand households.” However, the scenery before your eyes can no longer encompass half of Changsha as it did in the past. High-rise buildings now surround Tianxin Pavilion, with Yuelu Mountain still faintly visible in the distance, while the Xiang River disappears into the dense forest of tall buildings.

At the west gate of the park, there stands a clock tower known as the “警世钟” (Jingshi Zhong), which was built to commemorate the “Wenxi Fire.” In November 1938, as the Japanese army approached Changsha, the Kuomintang authorities adopted a scorched-earth policy and devised a plan to burn down the city. However, before the plan could be implemented, an accidental factor caused the fire to spiral out of control, turning Changsha into a wasteland. More than 3,000 people lost their lives, and 90% of the city’s buildings were destroyed. The people of Changsha paid the most tragic and heaviest price in their resistance against the enemy.

As I wandered through Tianxin Park and ascended Tianxin Pavilion, vivid historical scenes seemed to flash before my eyes, revealing the traces of Changsha’s tumultuous journey through the storms of time. Tianxin Pavilion has been repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt, yet it always stands tall and majestic. It carries the memories of countless older Changsha residents, weathering vicissitudes and remaining unyielding. The pavilion continues to stand firmly in the hearts of Changsha’s people, embodying the spirit of the Hunan people who remain steadfast in poverty and adversity, and unyielding in the face of danger.